The RPF Question

Amid blurry boundaries between fic, celebrity fandom, and conspiracy theories, how real person fiction evolved from forbidden to mainstream and back again.

by Sacha Judd

Elijah Wood, Orlando Bloom, Dominic Monaghan, and Billy Boyd at the Wellington premiere of The Fellowship of the Ring. Transformative fandom around the LotR actors marked a major milestone in the history of RPF.

This article is brought to you by Fansplaining’s patrons. If you’d like to help us publish more writing like this in the future, please consider becoming a monthly patron or making a one-off donation!

A Tumblr post crossed my dash recently, demanding that fans not “ship real people who play characters with each other.” In the midst of yet another round of Twitter discourse, I saw a post that read, “i hate rpf and i’m not afraid to say it. i hope every rpf writer gets cease and desisted to hell and restraining orders from the targets of their stalking and sexual harassment.” On TikTok, I stumbled upon a video with thousands of likes bemoaning new fans arriving in a rock fandom, ignoring the actual music in favor of a “new gay romance to obsess over” imploring shippers to “get a life.”

I remember reading the same sentiments ten years ago in the One Direction fandom, twenty years ago in the Lord of the Rings fandom, and thirty years ago before the web even existed. These hot takes can seem quaint to those of us who’ve watched attitudes toward real person fiction (RPF)—the transformative fan practice of shipping, writing stories, and creating fanart about real people—shift radically over the last three decades. But they also reminded me of just how much the boundaries and ethics of RPF have changed, and how the debate surrounding it still remains so incredibly fluid.

In the internet era—and especially with the rise of social media—we’ve witnessed an unprecedented increase in our access to public figures, the objects of our fandom. That’s led to collisions between celebrity culture, transformative fandom, parasociality, and conspiracy thinking. As a consequence, we’ve seen a full life-cycle in the acceptance of RPF, from something that was once seen as a completely taboo behavior to widespread tolerance and back again. And now, when our life online has consolidated into a handful of crowded platforms and fan communities have grown exponentially in size, we face a reckoning with the ethics of RPF in a world where few fandom boundaries remain.

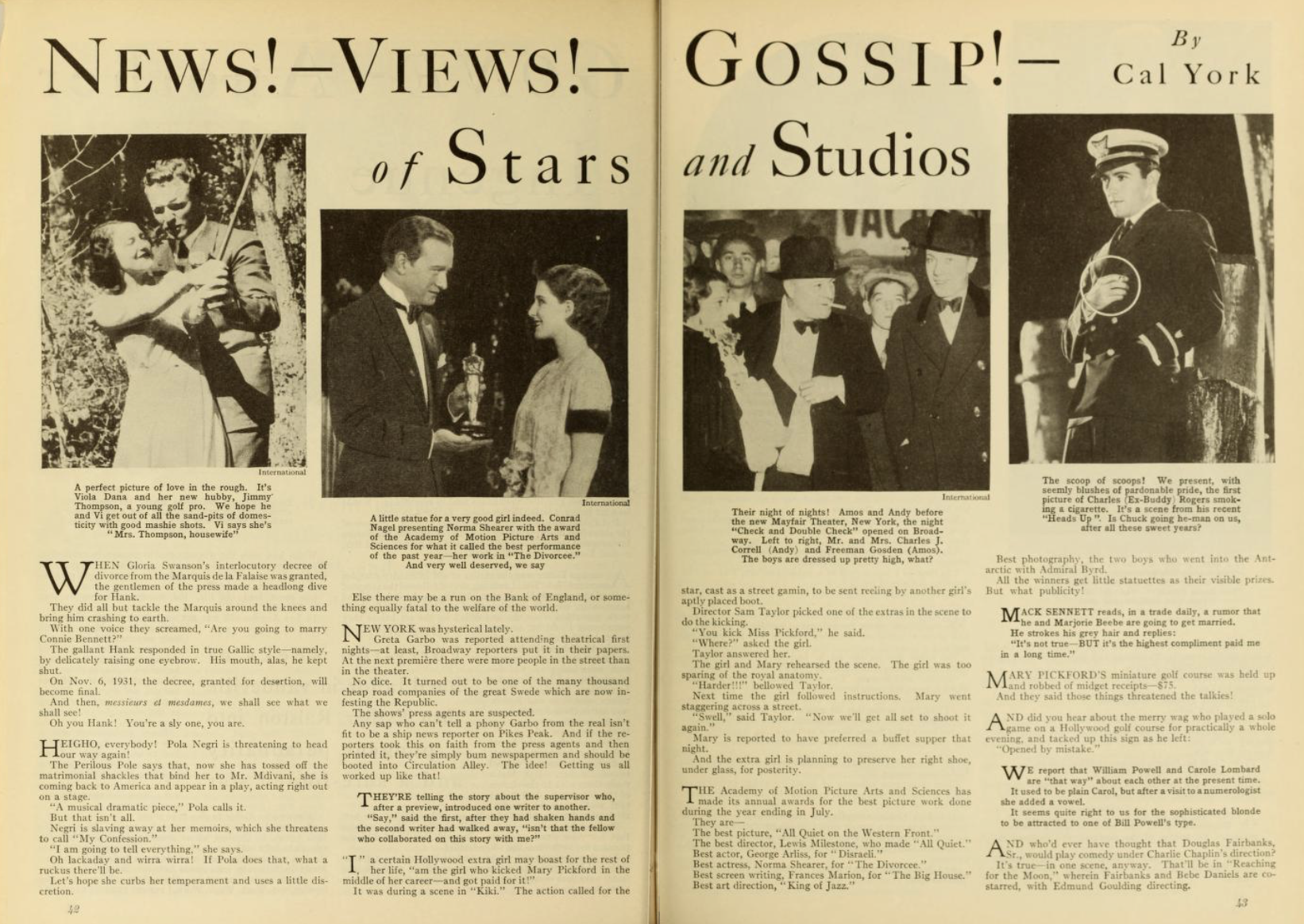

The urge to transform public figures into narrative protagonists has deep historical roots. Setting aside generations of self-insert stories penned about famous crushes in adolescent diaries, the history of real person fic traces back long before the internet to fan magazines and tabloid novelizations. In the Hollywood of the 1930s and ’40s, magazines like Photoplay and Modern Screen routinely featured speculative pieces about the private lives of actors and actresses, mixing facts with sensationalist gossip and thinly-veiled “what if” scenarios. These magazines encouraged readers to imagine hidden romances or secret struggles behind the studio-manufactured personas, a kind of proto-RPF.

“And they said those things threatened the talkies!” A scan from the January 1931 issue of Photoplay.

The fanzines of the ’60s and ’70s hosted the earliest examples of modern media fanfiction to be shared more widely. While the history of Kirk/Spock fic is well known, the Star Trek fandom also produced one of our earliest shared examples of RPF: “Visit to a Weird Planet,” which sees Kirk, Spock and Bones travel in time and meet the actors playing themselves on the show.

When the internet came along, those of us who made our homes in the earliest online fan communities gathered on Usenet. The pre-web internet was a small place, and for early adopters, Usenet sometimes offered a remarkably uncontrolled level of access to creators. Terry Pratchett would hang out in alt.fan.pratchett, adopting the nickname fans had given him, “Pterry.” Babylon 5 creator J. Michael Straczynski regularly contributed to the show’s newsgroups, and requested that fans not share fanfic there until the show was off the air.

In the mid-’90s, I first stumbled into alt.tv.x-files.creative, where “relationshippers” debated “noromos” over whether Mulder and Scully should kiss. Yet despite welcoming fanfic depicting every conceivable kink or monster, the community drew a firm line at RPF, enforcing a strict taboo that caused swift rebukes at any attempt to fictionally pair actors Gillian Anderson and David Duchovny. Group members’ opposition was varied: some thought the idea itself was “gross;” others felt that it was disrespectful given the actors were respectively married; still others felt that when fanfiction itself was being threatened by rights holders, involving actors would only put transformative fandom at greater risk.

In this era, RPF stories were seen as crossing a moral or privacy boundary, aligned with fandom’s broader “fourth wall” principle. In theater, a break in the “fourth wall” is when the illusion of a performance is disrupted and a performer addresses the audience directly—acknowledging the shared fiction everyone is participating in. But in fandom circles, “fourth wall” is commonly used to describe the illusion that actors, creators, showrunners and celebrities don’t pay attention to transformative fandom or even realise that it exists: that fandom is something we keep secret and safe from those we might be writing about.

In the precarious legal environment in which fanfic then existed—where authors like Anne Rice and studios like 20th Century Fox were threatening fanfic authors with legal action—RPF remained a bridge too far.

As the internet became more widely accessible, the once strictly patrolled boundaries of RPF started to erode. Social platforms took hold, and stars began directly interacting with fans. Gossip blogs and update accounts rapidly superseded the role of supermarket tabloids, and the personal lives of celebrities became content in their own right.

In music, the distinction between performer and stage character was already blurry, creating an ideal environment for RPF to flourish. As far back as the Beatles era, we have anecdotal evidence of fans engaging in roleplay and other RPF-adjacent activities, like imagining how their favorite stars would act in romantic situations.

At the turn of the millennium, online music RPF communities formed around “popslash” (*NSYNC, the Backstreet Boys) and “bandom” (Fallout Boy, My Chemical Romance, Panic! at the Disco). These fandoms were accelerated by the seemingly unending sources of new canon—music videos, interviews, touring performances, liner notes and lyrics—and by the participation of celebrities online. Musicians using Myspace and LiveJournal (and later, Tumblr and Twitter) to talk about their lives propagated “fanon”—widely accepted headcanons and interpretations, e.g., an artist’s personality traits or way of speaking—that made it into fic.

Panic! at the Disco, one of the core groups of “bandom” in the 2000s.

RPF fans were drawn to these music fandoms for different reasons. Popslash was often a reaction to the manufactured nature of boybands—RPF was a way to explore what the “real” people might be like behind the scenes. Bandom, on the other hand, centred on emo performers with soul-baring lyrics and the online presences to match; these emotive personas provided plenty of fodder for fans to incorporate into their stories.

The tension between the “real” and the “performed” personalities of these musicians came to a head with the discourse around the idea of “stage gay.” As music scholar Ross Hagen writes:

The proximity of the celebrity subjects created a number of issues for bandom authors and readers, but became particularly intense in a controversy over some musicians’ performances of “stage gay,” in which the performers groped, kissed, or flirted with one another onstage. This practice stirred controversy because the band members’ perceived support for and sensitivity towards feminist and queer communities was of paramount importance to many bandom participants, Some bandom participants felt validated by these onstage displays of affection, connecting it with the bands’ stated support for gay rights. Others thought that “stage gay” was little more than sexual identity tourism, given that a majority of the musicians were in heteronormative relationships and did not have to face the social consequences of queerness.

This form of controversy has continued with RPF ships in the present day, where K-pop fans debate the validity of “fanservice” from their idols, mainstream media outlets dedicate column inches to Harry Styles appearing on the cover of Vogue in a dress, and publications like the New York Times run commentary about Gaylor (the conspiracy theory that Taylor Swift is secretly queer and sending signals about it through her music).

When it came to fictional properties, a major shift in RPF came with one of the juggernaut fandoms of the early aughts: The Lord of the Rings. LotR fandom was absolutely ripe for RPF. Unlike most movie shoots, the young, attractive, relatively-unknown cast had spent two years in Aotearoa New Zealand filming the trilogy, and volumes of behind-the-scenes content was made available to the fans. The actors who played the Fellowship revealed they had gotten matching tattoos. Stories emerged of the parties and bars they’d turned up at in Wellington.

Fans loved seeing all of this—and some fans loved imagining they’d been having an extra good time together (one RPF fan site was called “Closer than Brothers”). In fanfiction and fanart, LotRiPS (Lord of the Rings Real Person Slash) creators depicted the stars falling in love on set. But as they would with any fictional fandom, they also penned alternate universes in which the actors were instead members of indie folk bands, or diner waiters, or teachers at a boarding school. And unlike the attitudes I encountered in earlier fandoms, RPF writers weren’t immediately drummed out of town—while they were still just a small part of an enormous fandom, LotRiPS thrived.

But LotRiPS also exposed the blurry lines between RPF and other kinds of celebrity fandom that continue to this day. For some fans, writing stories or making cute photo edits wasn’t enough. It wasn’t just that they liked imagining that, say, Elijah Wood and Dominic Monaghan might have made a cute couple. It was that they truly believed they were a couple—a secret one, unable to express their love because of the restrictions imposed by the terrible “powers that be” (in this case, New Line Cinema).

This sort of sentiment will feel horribly familiar to many of us now, but it was the LOTR fandom, appalled by the behavior of these excessive fans, that first came up with a name for them: “tinhats,” after the tinfoil hats we already associated with conspiracy theorists. And these tinhats would provide a template for conspiracy thinking about celebrities in the years to come, believing they were unable to tell the truth about their private lives, typically because—in the tinhats’ imaginings—the stars were being prevented from coming out of the closet by management, studios, record labels, or other mysterious forces.

It would be a mistake to think that the acceptance of RPF was linear, or progressed the same way in every fandom. By the end of the 2000s, like hundreds of thousands of others, I was hanging out in the Twilight fandom. The community was already enormous because of the books, but the movie adaptation launched it into the stratosphere.

Behind-the-scenes content flooded the internet, with clips of Robert Pattinson and Kristen Stewart looking cute together while filming in the Pacific Northwest. The mainstream media played up this dynamic; one glamorous Vanity Fair profile shoot made them look like a hot young couple in love. The outtakes: sunkissed, fingers intertwined, making each other laugh. You felt like you were in on a secret.

And yet, the taboo around RPF continued. For a fandom that shipped Robsten hard, any fic about the real couple remained underground. One notable story, "Two Thousand and Eight," circulated only as a Word document. Much later, I tracked the author down and asked her about it. She said, “no one really knows I wrote it. It's easy to find out if they do a little searching, but I've never really advertised it anywhere. RPF is very taboo in this fandom, and I know I shouldn't care, but I don't want to run off readers because they detest RPF.”

Robert Pattinson and Kristen Stewart photographed at an airport in France holding hands in November 2009.

Of course, it eventually became public knowledge that the actors had, in fact, been in a romantic relationship. Photographs of the pair holding hands broke the internet, and fueled the fire of subsequent conspiracy theories about celebrities and co-workers for years to come—one of the rare examples of tabloid fascination with co-stars finding love off-screen turning out to be accurate.

This was the same period in which the CW’s Supernatural was rising to transformative fandom dominance. It should go without saying that the premiere of a show about the hot and charismatic Winchester brothers immediately prompted fic about them as a couple (Wincest, as the fandom dubbed it). But it was perhaps because of that taboo—the idea of shipping brothers being too much for some fans—that the RPF ship “J2,” referring to actors Jared Padalecki and Jensen Ackles, emerged as another flagship community.

Once again, RPF flourished in many different directions. Some fans liked the actors so much that they wanted to picture them in alternate settings: a regency romance, a western, or (giving all of fandom a lasting gift) the original omegaverse. Other fans were fascinated by the actors themselves, writing fic that imagined life on set, after hours, behind the scenes. Much like the LotRiPS fandom, J2 thrived on the chemistry between people who spent long working hours together. Fans devoured behind-the-scenes interviews, convention appearances, and blooper reels—any scrap of casual interaction was potential fanfic fuel.

But while mainstream tabloids stalked the Twilight starlets, the same could not be said for Ackles and Padalecki. There was still something transgressive about RPF shippers engaging in a queer reading of straight celebrity lives, which continued to result in condemnation from some fannish corners: even among those who read and wrote it, some fans argued that RPF activity should stay on the downlow, so as not to be discovered by those outside fandom.

Over the next decade, RPF became more normalized in some of the largest fan communities on the internet. Fans not only had new tools for sharing and discovering fanfiction, but also more direct access to the celebrities themselves. The rise of social media platforms and streaming services transformed public figures into digital presences who felt instantly available and—sometimes organically, sometimes by careful publicist design—more relatable, fueling both the spread of RPF and the heightening of its controversies.

One of the most notorious examples of the 2010s was the “Larry Stylinson” phenomenon: fans who believed in, or at least enthusiastically imagined, a secret romantic relationship between One Direction band members Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson. As One Direction soared to worldwide fame, Larries parsed every facial expression, lyric interpretation, and backstage whisper for “proof” that the pair were in love but closeted by their management.

This mainstream boyband context took this activity out of the more obscure corners of fandom and placed it center stage, discussed openly on Twitter and Tumblr dashboards that bled into general celebrity gossip. While some Larry fans treated it as a fun fantasy or storytelling prompt (stressing the “f” in RPF stood for “fiction”), others adopted an evangelical fervor, insisting on the truth of the couple despite frequent public denials by the pair.

Eventually, those fans who just wanted to write stories needed to distinguish themselves from the conspiracists, creating a distinction between a “Larry shipper” and a “Larrie”. The intensification of parasocial relationships, shipping of real people, and “queering” celebrities who didn’t otherwise self-identify as queer deepened the ethical questions around privacy and consent, making RPF feel more fraught than ever.

The phenomenon of tinhatting has continued to grow and expand over the past decade and a half. Conspiracy theorists now pop up in virtually every fandom: convinced that Benedict Cumberbatch's marriage is a sham and his children are fake, or harassing church staff where Outlander star Catríona Balfe wed in an attempt to prove her marriage wasn't real. They pore over clips of Bridgerton’s Nicola Coughlan and Luke Newton looking for signs the pair are really dating, or decide that ice dancers Scott Moir and Tessa Virtue have chemistry on the ice because of their great love off it. A dedicated subset of Swifties dissect Taylor’s color choices and song lyrics for proof she’s on the verge of coming out, fueled by her love of leaving Easter eggs for fans, as if this is yet another puzzle to solve. For fans who are still able to draw a clear distinction between thinking two actors look cute together and assuming that the world is lying to them, tinhats make everything about RPF more complicated.

At its core, this debate involves overlapping and conflicting communities. The first group comprises those who consider themselves fans of an artist and are interested in consuming as much content as they can about them—even where this content might not be “official”, encompassing paparazzi shots, blind items, gossip columns, and fan selfies.

The second group are those who express that interest through transformative fandom, but consider the celebrities fictional constructs about whom they can write or create art without knowing or engaging with the “real” person at all. For these fans—for example—the Lewis Hamilton they write about may bear little to no relationship to the real F1 champion, and that doesn’t matter. It’s a character constructed by fandom, and transformed in the same way a fictional creation might ordinarily be.

The third and final group, the tinhats, believe that they have uncovered some hidden truth that the celebrity may not be willing or able to reveal.

At the heart of all this are the central questions that get at the shifting boundaries and ethics that inform RPF. Is it possible to draw a line between conspiracy theorists invading the actual private lives of celebrities, and “good fans”? Is a “good fan” someone who just wants to enjoy the music, or the sports game, or the movie—or can it also be someone who wants to write stories or create art about the perceived private lives of public figures?

The 2010s also saw a surge in RPF focused on a wider range of public figures, from professional athletes to new-media stars to political pundits (and even politicians themselves). Hockey fandom set the sports RPF standard: transformative fans, many of whom were newly introduced to the sport through Tumblr’s curated gifsets and highlight reels, brought the same narrative instincts they applied to fictional characters to real-life players. Interactions at practice, photos from charity events, and playful interviews became the building blocks of stories that imagined athletes in complex personal and romantic relationships.

A perfect storm arose in 2012, with fandom fourth walls eroding across the board, an NHL labor dispute shortening the season and forcing mainstream sports outlets to cast around for topics to cover, and one player even tweeting a link to a slash primer about himself. Hockey fandom was used to hyper-masculine fans in it for the fights—and stereotypical “puckbunnies” in it for the players. The idea that there were women online writing stories about players in gay relationships with their teammates was unexpected and noteworthy.

This unwanted attention led many fans to ensure their works remained hidden behind friends-locked accounts or AO3 privacy settings, a practice that continues to this day. Hockey RPF reflected fandom’s expanding scope, as fans moved to follow the NHL from other fandoms. The ‘why’ of it is complicated: fandom migrations are often a function of network effects (fans move along with their communities) and there are a range of similarities in the fictional treatment of, say, boybands and sports teams. All of this underscored the friction between fandom’s imaginative freedom and the professional realities of public figures who never signed up to be part of a “story.”

Sidney Crosby and Evgeni Malkin, captain and alternate captain of the Pittsburgh Penguins—and one of the most popular ships in hockey fanworks.

The 2010s also gave rise to an entirely new category of celebrity: the digital-native star. YouTubers like Dan Howell and Phil Lester—shipped as “Phan”—shared a kind of intimacy with their audience that seemed entirely novel. Their online personas felt authentic and spontaneous, recorded in bedrooms and broadcast directly to fans’ screens. Fans responded by writing thousands of stories about them, from realistic relationship dramas to wild alternate universes.

Unlike film or TV actors, whose performances were understood as separate from the individual, YouTubers seemed to offer their “real” selves as their primary content. This made the lines between reality and fiction even more tangled. With little barrier between a YouTube creator’s daily vlogs and a fan’s imagination, the ethical debates around RPF intensified: Was this all harmless fantasy, or an intrusion on a person’s sincere self-expression?

This era also saw a subculture of political RPF, focused on both political figures and adjacents like news anchors and pundits. Some of this was born out of the same sorts of cues as any other RPF fandom—the idea of people spending long hours on the campaign trail, photos or footage of people who seemed close to one another. “Third Monday” was a President’s Day ficathon for American political-minded fandoms, including fake news RPF like Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert and real news RPF like Anderson Cooper. Barack Obama/Rahm Emanuel was a popular ship, and there were crossovers with The West Wing and Newsroom. In the Trump era, RPF was also used as a way to take back control or power over fictional versions of unpopular politicians.

By the late 2010s, RPF was no longer a hush-hush corner of fandom. It became standard for large fandoms surrounding genre television shows to have parallel RPF sub-communities, creating tension between fans. It popped up in trending Tumblr tags, on fic platforms like Wattpad and AO3, and even in mainstream gossip media which occasionally discovered (and sensationalized) these fan practices. This heightened visibility provoked soul-searching throughout fandom culture. Some communities implemented strict tagging and privacy measures, encouraging creators to lock RPF works behind membership walls.

In this landscape, what had once been niche was now woven into the tapestry of everyday fan practice. RPF had gained traction as another mode of transformative work, readily recognized and discussed alongside ships from fictional source material. But as it became more common, it also became more controversial, setting the stage for the ethical and interpersonal reckoning that would define the next phase of fandom’s evolution.

Fantasizing about celebrities is a harmless endeavor, and discussing those fantasies with friends is a time-honored tradition. The very concept of a “free pass”—an agreement between significant others that if one of them meets their nominated celebrity, they’re allowed to cheat with them—enshrines the idea that thinking about these things is common.

Criticisms of RPF often stem from the idea that it somehow takes these “harmless” fantasies a step further: imagining a celebrity to be queer when they’re not, or imagining them in romantic or sexual relationships with co-stars or friends. Or even worse, drawing a celebrity’s attention to these fannish practices—breaking that fannish “fourth wall.”

But if you google “celebrities reading fanfiction,” you’ll find any number of examples of stars being confronted with stories about their characters or themselves. These segments are always played for laughs, finding the kinkiest or most explicit or most poorly written works. Chat show host Graham Norton had Daniel Radcliffe read fic about himself in 2012. Author Caitlin Moran awkwardly insisted that Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman read from a Sherlock fanfic at the show’s third-season premiere at the British Film Institute in 2013.

Even though fan backlash to these spectacles seemed to stop it happening for a while, a decade later—in 2022!—the British television network C4 announced The Really Really Rude Puppet Show, to be hosted by beloved Bake Off star Mel Giedroyc, in which celebrities would read fanfic about themselves to be acted out by puppets. Fortunately, this stale idea seems to have floundered in development.

Hosts of Taskmaster (UK) Greg Davies and Alex Horne, bantering in series 1. Yes, they routinely hold hands.

Of course, the range of reactions from the subjects of RPF is as varied as the stories themselves. When questioned, many stars take a diplomatic stance along the lines of, “it’s not for me, I don’t read it.” In contrast, Greg Davies and Alex Horne, presenters of the UK television game show Taskmaster, have leaned heavily into jokes about the RPF about them. I have one famous friend who remains furious that he only appears as a side character in two stories on AO3 and only has one speaking line. To each their own.

For many RPF fans, the idea that the subject of their work might see it is mortifying. But while A-List celebrities like the stars of the MCU are not hanging out in the same social spaces online as fans, a new generation of fans have grown up around digital creators, TikTokkers, podcasters, and influencers, who depend on a constant and reciprocal relationship with those fans for their income. These smaller fandom spaces pose even greater challenges when it comes to RPF. Authors in the fandom for podcast Pod Save America, for example, were forced to take all their fic private when someone posted links to stories in a forum where producer Crooked Media employees were members.

The internet's evolution from niche subculture to dominant culture has fundamentally changed how we engage with celebrities and fan communities. Where fans once gathered in carefully moderated spaces with clear boundaries and shared norms, we now find ourselves in vast digital town squares where everything happens in public view. The proliferation of social media creates an illusion of intimacy. There is no “safe space” in which to explore our fannish obsessions when everything is happening on main.

In the current video-first, algorithm-driven environment, RPF continues to flourish. To the surprise of anyone around when One Direction was at its height, the pandemic saw a surge in new Larries—young fans who were encountering (and clipping, and sharing, and reacting to) the old video content for the first time. On- and offscreen chemistry between the stars of shows like Interview with the Vampire and The Bear have fans poring over their interactions during promotional tours.

The offscreen chemistry between onscreen lovers Sam Reid and Jacob Anderson—who dubbed themselves “Jam Reiderson”—is a major component of discussion in Interview with the Vampire fandom.

In transformative fan spaces, there are still thousands of fans invested in writing stories about their constructed versions of celebrities, whether it be K-pop idols, F1 drivers, or Thai BL actors. For these fans, the distinction between their version and the real person remains clear. In the BTS fandom, for example, some fans refer to an “AO3” version of the characters to distinguish the fandom’s creations from the actual stars.

But outside these transformative fan spaces, the search for signs and signals, like who stood beside whom on a red carpet, or which stars were paired together for interviews, continues unabated. More than ever fans expound on their “theories”—not just about how a White Lotus season might end, or which fictional firefighter ship will be canon on 9-1-1—but about whether the Challengers actors enjoyed more than their onscreen time together, disclaimed with the oft-repeated meme phrase “which could mean nothing” (which itself comes from the supposed romance between Ben Affleck and Matt Damon).

It’s this contextless environment that leads to the kind of bold proclamations that RPF is sinister: to young fans stating DNI (do not interact) to those who like RPF, and to the kind of flattening effect that has some newcomers to fandom being told that any kind of shipping at all is inappropriate.

As fandom continues to mainstream and we embrace more open discussions about shipping, fantasies, and transformative works, we face a crucial challenge: maintaining respect for real people's privacy and consent while preserving the creative freedom that makes fandom special. The solution may not lie in returning to the strict taboos of the past, but in developing new community norms that acknowledge both the reality of our online lives and the importance of ethical boundaries.

The future of RPF in fandom culture depends on how we navigate these competing demands. Can we create spaces that allow for creative expression while respecting personal boundaries? Can we maintain the magic of transformative fandom while acknowledging that the subjects of our stories are real people with real lives who inhabit the same public spaces that we do?

As we exist in an era where fandom, celebrity culture, and personal privacy overlap more than ever, the true challenge lies in how we build and maintain our communities. While fandom is about creative joy and communal storytelling, it has to also grapple with the moral weight of depicting real lives. The way forward involves fostering dialogue instead of shutting it down, championing respect, and finding a space between delighting in public personas and intruding on private lives. Only then can fandom remain both vibrant and accountable in our interconnected world.

If you liked this article, please help us make more! Become a patron for as little as $1 a month, or make a one-off donation of any amount.

Sacha Judd is a writer based in Aotearoa New Zealand. She’s spent the last decade speaking about the intersection of the tech sector and fan communities at conferences like Velocity, Webstock, and Beyond Tellerrand. She has written on these topics for Letterboxd’s Journal, The Spinoff, Pantograph Punch, and has been quoted in Teen Vogue and Rolling Stone. You can subscribe to her newsletter here.