Bridgerton and Period Drama Fandom’s Enduring Racism Problem

Complaints about historical accuracy and acting quality are often dog-whistles: some fans only want to see white actors—and white history—on screen.

by Amanda-Rae Prescott

Simone Ashley as Kate Sharma in Bridgerton. Image courtesy Liam Dianiel/Netflix.

This article is brought to you by Fansplaining’s patrons. If you’d like to help us publish more writing like this in the future, please consider becoming a monthly patron or making a one-off donation!

The first season of Bridgerton made a massive splash at the end of 2020. Fans had waited years for that kind of big-budget historical romance series, and posters and trailers featuring Regé-Jean Page, who would play love interest Simon Basset, the Duke of Hastings, made millions swoon in anticipation.

But while many people loved that Page was moving from overlooked actor to leading man, there was immediate backlash—because Simon in the Bridgerton books is white, and Page is Black. To protest his casting, racists created the trending hashtag #NotMyDuke, insisting Simon should be played by a white actor. Netflix didn’t acknowledge the racist responses: Page’s interviews and Netflix PR focused on the positives of racial diversity on Bridgerton before and after the premiere in December 2020. This pattern set the tone for future incidents to escalate in severity.

A Netflix adaptation of eight romance novels by Julia Quinn, the show follows the Bridgerton siblings in a fictionalized rendition of the Regency Era as they find romance and secure marriages to continue the family fortune. The Bridgertons are all played by white actors in the television series, while several of the love interests and supporting characters are played by Black, South Asian and East Asian actors.

Partly because of the scale of Netflix, the Bridgerton fandom is massive, and fan discussions frequently escalate to arguments over favorite characters, actors, and relationships. There are divides between fans who have read the original novels and don’t want the television canon changing plot lines; fans who are OK with the television canon differing from novel canon; and fans who have only watched the television series and do not care about the novels. The global nature of the fandom often means fans are bringing their own cultural, religious, ethnic/racial, and gender/sexuality biases to their interpretations of Bridgerton canon. This creates a perfect storm for flame wars and harassment—which often centers on the racebent cast.

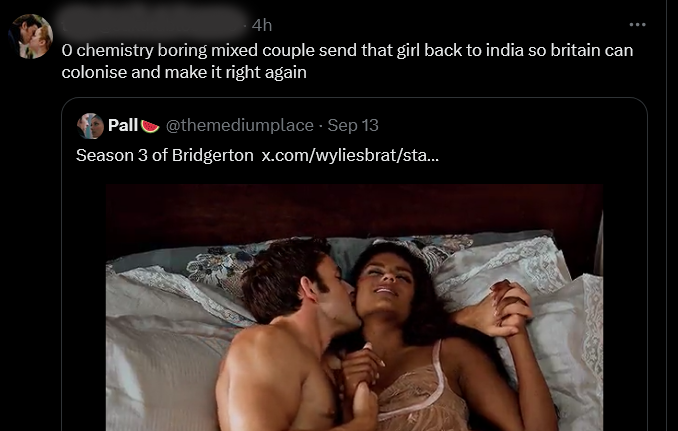

Some of the racism in the fandom is coded—but plenty of it is overt. Take, for example, a fan’s now-deleted Tweet about a Season 3 promotional image:

While this incident is an extreme example, it’s indicative of trends in the wider Bridgerton fandom around racist commentary on BIPOC characters and cast members. Three seasons in, there’s still an active segment of Bridgerton fandom who refuse to accept that Bridgerton will continue to cast actors of color as love interests for the Bridgerton siblings and as members of the Ton (a period term for high society). The all-white world of the novels has long been abandoned.

Racists frequently post insulting comments towards the BIPOC actors and tag their accounts in abusive commentary—and this behavior has continued despite numerous attempts by other fans to call them out, as well as pleas for Netflix to intervene. Actors who don’t have social media accounts are not safe from online harassment, either, because some feel emboldened by the idea that the actor cannot read their comments. Some fans have even gone as far as accusing Netflix and Bridgerton’s production company, Shondaland, of encouraging racially biased treatment, which Buzzfeed recently reported on.

Anti-Black racism is still rampant in the fandom—as the end of Season 3, which aired last spring, has proven. Not only did racists attack the show for casting Victor Alli as Scottish earl John, they also attacked actor Masali Baduza for playing Michaela Stirling, a race and genderbent version of John’s cousin, Michael. Baduza and Michaela were also targeted by angry homophobes, because the series was potentially introducing a queer romance plotline.

Bridgerton fandom is far from the only example of racism around period drama television. There’s a continual tug of war between audiences who want to see BIPOC in historical fiction stories where racial trauma doesn’t exist, and people who only want white supremacist narratives catered to. They don’t just want to deny BIPOC fans the same level of escapism white fans have enjoyed for years—they want to put an end to any BIPOC actors appearing in period dramas, full stop. Racists weaponize outdated, inaccurate, or politically distorted history to attack characters and casting. Rather than a reference to era-specific set design or correct dates of important events in scripts, the concept of “historical accuracy” has become a very specific dog-whistle.

Fans have the power to mute or block users or pages they don’t want to see on social-media platforms, but can more be done? Can the entertainment industry use their resources to confront racists online? But before that question can be answered, it would be helpful to analyze the trends that existed before the very first fan complained about Simon.

Most period dramas in the early decades of television were adaptations of classic literature or dramatized biographies and other historical events. Many of these older programs presented an “idealized” past where there were no BIPOC characters, and the histories of colonization, chattel slavery, and racism were either completely hidden or glorified. These “historical” dramas ran counter to actual history: historians have definitively proven that BIPOC histories are closely intertwined with both UK and European history from ancient Greece and Rome to modern times.

With a few exceptions for productions where slavery and/or colonialism were directly portrayed, there were no actors of color in early period dramas. But by the turn of the 21st century, more BIPOC actors were being cast in traditionally white roles—a practice known as “color-blind,” racebent, or inclusive casting. (Some have stepped away from using the term “color-blind” casting due to the implications of consciously ignoring racial bias, and in an attempt to reduce harm to the disability community from ableist language.) This is different from “color-conscious casting,” where a BIPOC actor is cast in a traditionally white role which has been rewritten to include ethnically/culturally relevant historical or personal background information.

Both of these practices have their roots in UK theatrical productions hiring Black actors to play leading roles in Shakespeare and other works. Black actors have been on European and American stages for centuries—see Ira Aldridge in 1825, who took on many roles ostensibly written for white actors. The Royal Shakespeare Company began inclusive casting as early as the 1960s, but took it on in earnest in the 1980s.

When the practice eventually reached film and television, early examples were rooted in fantasy and science fiction, like the 1997 version of Cinderella starring Brandy. Historical dramas were slower to adapt to a wider casting net, even for stories where race or ethnicity were important elements—for example, when the 1995 BBC/PBS adaptation of The Buccaneers cast a white Italian actor to play a Latine character.

The earliest example of racebent casting in a UK TV period production is the 2005 BBC Casanova limited series. Showrunner Russell T. Davies was also in charge of the revival of Doctor Who, which premiered that same year. Davies frequently used BIPOC actors in major and supporting roles on Doctor Who. Other BBC productions followed suit: in 2008, Black actor Angel Coulby was cast as Guinevere in Merlin.

These early efforts continued to spread, especially with continued activism and industry initiatives to increase racial representation. More and more productions began restoring previously whitewashed characters or history by consciously casting BIPOC characters, introducing new original characters based on real historical biographies, and racebending previously white characters.

Unsurprisingly, the spread of inclusive casting also prompted racist blowback. Some critics focused exclusively on productions they believed were “distorting” biographical history, while others focused on criticizing inclusivity with entirely fictional characters. The end goal of both sides of these critiques was the same: to decrease opportunities for actors, and chances for audiences to see themselves in media.

Some productions chose to cast diversely in order to restore lost or whitewashed history. In 2011, Black Irish actor James Howson suffered a mental health crisis after enduring months of death threats and harassment for portraying Heathcliff in the 2011 film adaptation of Wuthering Heights. (Literary scholars argue that Emily Brontë’s text clearly describes Heathcliff as having either Roma, South Asian, or African ancestry—and with the announcement that white actor Jacob Elordi will play the character in Emerald Fennell’s new film adaptation, fan discussion of the 2011 film has been renewed.)

The 2019 television adaptation of Phillipa Gregory’s The Spanish Princess, which combines fictionalized elements from Catherine of Aragon’s marriage to Henry VIII, came under fire for refusing to whitewash Tudor England. (The series prominently featured her lady-in-waiting Lina and her soldier husband Ovieido, who were Spaniards of African Moorish descent; historians have extensively documented that Tudor England did not have the same level of racism as later centuries, when the African slave trade was established.) The 2022 Anne Boleyn limited series starring Jodie Turner-Smith also was attacked by British racists, who couldn’t understand that a Black actor was playing a fictionalized Anne Boleyn, not depicting her in documentary format.

Jane Austen adaptations have also been targets of controversy over racebent and inclusive casting. Sanditon, the television adaptation of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel, was accused of “inaccuracy” when Crystal Clarke was cast as Georgiana—despite Austen describing the character as having mixed white and African ancestry. Alongside outright racism towards Georgiana, some fans used pineapple emojis to represent their support of the show. This may seem like an innocent action—but the pineapple was explicitly used as a symbol of slavery and colonialism in the series. (The controversy was quickly dubbed #PineappleGate.)

Crystal Clarke as Georgia in Sanditon. Image courtesy Joss Barrett/MASTERPIECE .

Fictional historical dramas with BIPOC characters have drawn similar racist backlash. Viewers complained when shows including Downton Abbey, Call the Midwife, Endeavour, Outlander, and Poldark added or increased the screentime of Black supporting characters—which often forced other characters to question prevailing attitudes on race. (Outlander, it should also be noted, was criticized for failing to condemn a key character as a slaveowner.)

Other productions offered opportunities to actors from diverse backgrounds without changing any aspects of the characters or plots. The 2018 PBS/BBC adaptation of Les Miserables received far more angry comments about David Oleyowo playing Javert than about the fact the limited series was not based on the musical. Dev Patel faced similar blowback when he was cast as the titular character in 2019’s The Personal History of David Copperfield. And when the 2023 PBS/ITV adaptation of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones featured Sophie Wilde as the love interest, some fans of the novel were not pleased about her casting.

Netflix’s 2022 adaptation of Persuasion stirred up a hornet’s nest of reactions from Austen fandom: while some fans disagreed with the style of the adaptation, it was clear that there was racism brewing underneath the surface of some critiques. Mr. Elton, the Musgrove sisters, and other supporting characters were cast with BIPOC actors. Fans on Facebook were sharing a photoshopped poster with the Persuasion cast from a British film series that depicted offensive stereotypes. Even though Austen’s work—notably Mansfield Park—explicitly dealt with slavery, for some, the thought of Austen adaptations acknowledging the fact was too much.

The continuing attacks on Bridgeton and other diverse casting in TV and film have resulted in a backslide of acceptance, even in the theater world. Despite the fact that UK theater companies have used racebent and racially conscious casting for decades, in 2024, Francesca Amewudah-Rivers received death threats for playing Juliet in a West End production of Romeo and Juliet, part of a targeted online harassment campaign spurred on by right-wing British activists. This backlash is notable because there was nowhere near this level of vitriol when another Black actor, Condola Rashad, played Juliet on Broadway just a few years earlier.

These diversely cast works changed the narrative, forcing future creatives to reverse past casting discrimination, and consider how fiction can be used to teach audiences about these hidden histories. The goal of racist discourse in period drama fandoms is to return period drama to only showing whitewashed propaganda. Some may hide behind critiquing “modern writing” or “actors being not up to par,” but these are dog-whistles for their true opinion: that they only want to see white actors—and white history—on screen.

With Bridgerton, the fandom’s racism issues echo the patterns of these earlier period drama controversies—but they’re magnified due to the fandom’s vast international and incredibly active audience. Because the fandom is so large, spans many social media platforms, and has entire spheres in different languages, it’s very easy for the average Bridgerton fan to never see the worst examples featured here. Racist posters frequently end up deleting posts—or in some cases, entire accounts—after antiracist fans call them out. (In addition, many accounts and posts have been deleted in the past year due to the instability of social media platforms like X/Twitter and TikTok.)

The Bridgerton novels were published from 2000 to 2006, so fans who first found the story that way predate the TV show fandom by many years. In the novels, there are no BIPOC main or even secondary characters; one love interest later in the series was even depicted as previously working for the colonizing East India Company. Diehard book purists were never going to be happy that their favorite white love interests were played by nonwhite actors in the TV series. They believe the characters belong only to them, and frequently lash out against fans who are only interested in the show.

Since Season 1, Bridgerton fandom has had controversies stemming from the racebent casting as well as fans applying racial stereotypes to BIPOC characters onscreen. The show’s writers changed some character backstories and timelines to factor in ethnicity—but not all. BIPOC fans have pointed out that much of the racist and homophobic commentary comes from white women who are angry that the show is departing from the novels, and providing escapism to BIPOC and queer fans.

When Regé-Jean Page announced he was departing to pursue other roles, many fans ironically called him “ungrateful” for leaving—even though they were actively harassing him on social media. (Some of this harassment involved highly inappropriate sexual fetishizing comments as well.) Fans accused other cast members of liking mean posts about the situation, and Page continues to attract abusive comments about his career (in contrast to his white co-star, Phoebe Dyvenor, who also had a reduced role in Season 2 and declined to return for Season 3).

British historians complained about the series casting Golda Rosheuvel as Queen Charlotte—complaints that resurfaced during the premiere of her titular limited-series prequel, with India Amarteifio in the lead role. Ruby Barker, the Black actor who played Marina, a love rival to one of the white characters in Season 1, also faced online racist harassment. Since her departure, Barker has claimed in interviews that Netflix and Shondaland are guilty of failing to defend her from the trolling, which prompted a mental health crisis. (Racists continue to falsely claim Barker was lying about her trauma.)

Season 2 also introduced two new racebent characters played by South Asian actors: sisters Kathani “Kate” Sharma, played by Simone Ashley, and Edwina Sharma, played by Charithra Chandran. Both sisters were interested in Anthony Bridgeton, and Netflix initially marketed the season as a love triangle—despite the fact many fans already knew the book plot. This led many fans to pit Kate and Edwina—and the actors themselves—against each other. Kate and Edwina were shown together on posters with Anthony and fans ended up photoshopping a poster with just Kate and Anthony; Chandran left Twitter after fans started tagging her in insulting tweets about being edited out. And while Ashley was the lead of the season, the fact that Netflix PR focused on promoting the show as an ensemble versus promoting her as a solo star remains a sticking point in the fandom, with many BIPOC fans convinced this sidelining was motivated by colorism and racism.

The Sharma sisters weren’t spared from critiques from the South Asian diaspora, either, many of which were based on colorism and casteism. Some believed Ashley was “too dark” to play the role of an upper-class woman, and Kate’s return in Season 3 attracted racist commentary on TikTok and other platforms. Many in the South Asian diaspora were also upset by one of the official Netflix accounts promoting a fanart image of white characters from Season 3 dressed in traditional Desi attire, especially after they felt the Sharma sisters received less screen time and development in Season 3.

Ashley was the subject of many racist posts before and during Season 3; unfortunately, some of these only survive in screenshots. These posts included body shaming on top of colorist and racist commentary. Even casual fans and observers outside the fandom noticed some fans preferred Season 3 to Season 2 because it was the only season where the main couple were both white. Some fans also attacked Ashley by making biased comparisons between her and her white costars. Black and South Asian fans have actively pushed back on racist tweets, but unfortunately, some fans have continued to dig their heels in and claim Black fans are wrong for wanting the fandom to do better.

Isabella Wei, Katie Leung, and Michelle Mao as members of Sophie’s stepfamily. Image courtesy Liam Dianiel/Netflix.

Season 4, which is wrapping up filming now, continues the series’ racebent casting with Australian-Korean actor Yerin Ha as Season 4’s love interest, Sophie. Within the fandom, this has already increased anti-Asian racism, colorism, and conflicts within East and Southeast Asian diaspora communities. Fans are also fiercely debating the announcement that British-Chinese actors Katie Leung, Michelle Mao, and Isabella Wei are playing Sophie’s stepfamily due to historical conflicts between China and Korea both before and after the era in which Bridgerton is set. Many fans also believe it’s unfair that Ha received a warmer welcome from fandom than Masali Baduza did—and think that racism and colorism are the cause. On the Bridgerton Facebook and Instagram pages, fans continue to complain about the racebent casting conflicting with the novel descriptions of Sophie and her family.

Sophie’s plot in Season 4 has the potential to unify fandom with swoon-worthy moments and iconic costumes that fans are going to want to wear. But if the trends of prior seasons aren’t reversed, it’s safe to expect similarly intense conflicts. The first three seasons have set a blueprint: there will be a new round of ship wars as fans constantly compare romance tropes; arguments over changes to the original novel will continue to stir up controversy; and the way Sophie’s story develops is highly likely to fuel more East Asian diaspora infighting.

To counteract these issues, many Sophie fans will likely form alliances with fans of the other BIPOC canon characters—aside from the shared interest in these characters, these fans all want to defend the ability to see themselves in Bridgerton. And if BIPOC fans believe that new white characters are taking screen time away from established characters of color, racist fans will also attempt to deflect and derail discussion.

Is it possible for Bridgerton fandom to correct course? While fans cannot control what PR, press, and actors do, fans individually and collectively can change the conversations they encounter in the fandom. White and non-Black POC fans need to take on the work of harm reduction in Bridgerton and other period drama fandoms. Fans can screenshot, report, and block racist commenters—and they can also deny the spotlight to bad-actor trolls who thrive on negative attention. Fans who moderate Bridgerton discussion spaces can ban racist discourse in their groups, and remove members who refuse to change. This kind of proactive response is more important than ever, with Bluesky and other newer platforms emerging to discuss Season 4 and beyond.

Bridgerton fans can also look to other period drama fandoms’ changing reactions to racebent or culturally conscious casting. Grantchester fans on both sides of the Atlantic have adjusted well to Rishi Nair replacing Tom Brittney as an Anglican vicar who solves mysteries between Sunday services. Fans have praised Alphy Kottaram’s optimistic outlook on life, and the way the series has been addressing racism against British citizens of South Asian descent. The BBC/PBS co-produced series World on Fire featured Black British, Black French, and Indian characters based on real World War II military and social histories with a “take it or leave it” approach, and its fandom has embraced the racially diverse actors and storytelling.

Rishi Nair as Alphy Kottaram in Granchester. Image courtesy Kudos, ITV and MASTERPIECE.

In the period drama world, there’s at least one example where confronting racist complainers with historical evidence or a clear defense of cast and crew worked to correct negative fandom discourse. In 2020, the new adaptation of James Herriot’s veterinary memoirs All Creatures Great and Small featured an interracial farmer couple who had a border collie in labor. Racist British viewers claimed that the storyline was “not realistic,” but dissent quieted down when one of the actors revealed that the character was based on the real family history of his co-star.

Period dramas aren’t going to stop casting diversely anytime soon—but fans monitoring themselves and each other may not be enough to solve the problem of racism in these spaces. Many social media platforms have abandoned moderation or have changed algorithms to reward bad behavior. One tool that’s often underutilized is flagging racist fan content as violating platform rules on copyright laws. (Copyright violations are taken down much faster than reports of hate speech, since social media companies do not want to be sued by studios.)

But BIPOC actors and fans need more studios and streamers to confront racist fans directly. A good example is Rick Riordan’s official response to racists attacking Disney+ for racebent casting on Percy Jackson and The Olympians. Some big Hollywood franchises have social media professionals monitoring and deleting racist comments online, but it’s clear that Bridgerton—along with the BBC, ITV, PBS and other frequent period-drama production companies—have either an “ignore the trolls” approach to social media engagement, or are barely aware of online fandom. This is a bad business strategy—these days, online public opinion is increasingly more influential than critics and journalists. And not all of this influence comes from people who care about these shows: some online “critics” of British period dramas are in fact political influencers with an agenda, aiming to weaken public support of government arts and funding along with silencing marginalized audiences.

All of the money spent on positive advertising is useless if the first thing BIPOC audiences see online is racist viewers complaining about “woke casting.” The goal of racists is to turn audiences away from Bridgerton and other diverse period dramas. The upfront costs in training and hiring moderators, consultants, and social media experts is in the end cheaper than losing revenue because potential viewers decided to watch a competing show—or because fans of color didn’t feel like there was a space for them, online or onscreen.

If you liked this article, please help us make more! Become a patron for as little as $1 a month, or make a one-off donation of any amount.

Amanda-Rae Prescott is a freelance journalist specializing in British television news and fandom issues for Den of Geek and GBH Drama. She also has bylines in BBC History Extra and Doctor Who magazine. You can find her on Bluesky as amandaraeprescott.