Episode 140: Miranda Ruth Larsen

In Episode 140, Flourish and Elizabeth interview Miranda Ruth Larsen, a media studies scholar who focuses on K-pop, anime, and horror. They dig into the 2020 spotlight on K-pop in Anglophone spaces, the concept of “affective hoarding,” and her essay in the anthology Fandom, Now in Color, on her experiences as a multiracial American researcher in Japan. They also revisit the last episode’s conversation on queerbaiting and viewer expectations, and read two listener letters on the Supernatural finale.

Show Notes

[00:00:00] As always, our intro music is “Awel” by stefsax, used under a CC BY 3.0 license.

[00:01:28] These letters are responding to our last episode, “The ‘Q’ is For ‘Queerbaiting.’”

[00:03:19] That Hollywood Reporter podcast: “‘TV’s Top 5’: How ‘Saved By the Bell’ Honors Its Past; CW Chief Bids Farewell to ‘Supernatural’”

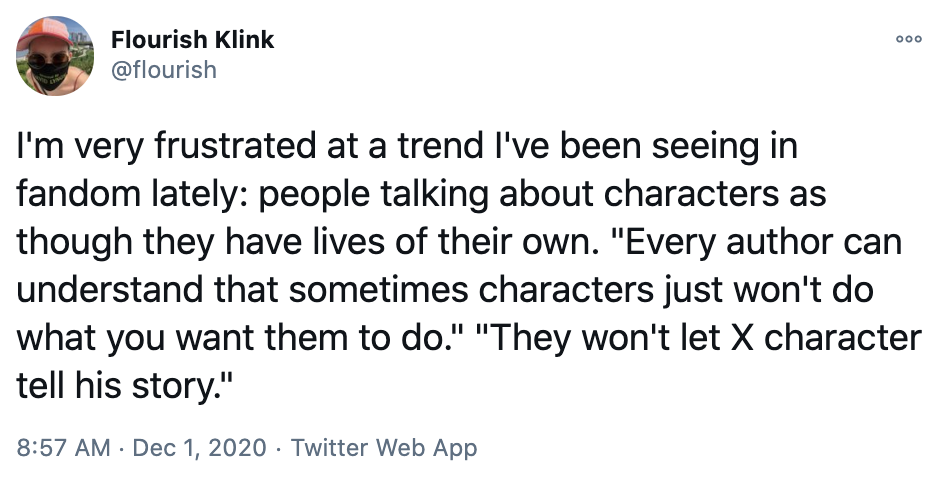

[00:14:04] Click through for Flourish’s full thread on character:

[00:19:34] Misha Collins’s comments were also a whole thread, but the relevant tweet:

[00:22:52] The interstitial music here and throughout the podcast is “The Little Painter Man” by Lee Rosevere from Music For Podcasts 6, used under a CC BY 3.0 license.

[00:25:19] Yes, Miranda has written about Gackt in an academic context! “Fan Service: Gackt,” in the University of Tokyo Japanese Media Keywords.

[00:46:20] Miranda spoke about this in “K-pop’s Online Activism for Black Lives Matter is Complicated,” an episode of Vox’s “Reset” podcast.

[00:46:45]

[00:55:10] In case you missed it: Lana Del Rey hated longtime rock critic Ann Powers’ review of her album Norman Fucking Rockwell. And said so on Twitter.

[01:06:25]

Miranda with Daehan and Mingyu of RE:ACT (formerly CIRCUS CRAZY) at K-Stage in Tokyo in 2018.

[01:07:26] Miranda wrote about affective hoarding in a post for On/Off Screen.

[01:13:40] Miranda’s essay, “‘But I’m a Foreigner Too.’ —Otherness, Racial Oversimplification and Historical Amnesia in Japan’s K-pop Scene,” appears in Rukmini Pande’s anthology Fandom, Now In Color.

[01:16:42] In June, we spoke with Keidra Chaney in Episode 128, “The K-pop Narratives.”

Transcript

[Intro music]

Flourish Klink: Hi, Elizabeth!

Elizabeth Minkel: Hi, Flourish.

FK: And welcome to Fansplaining, the podcast by, for, and about fandom!

ELM: This is Episode 140, “Miranda Larsen.”

FK: I am so excited to get to speak to Miranda Larsen, a scholar of K-pop, among many other things.

ELM: Many other things: media studies, fan studies, there’s a particular concept that Miranda has articulated called “affective hoarding” about, in 10 words or less: fans who get joy out of denying other fans things. I didn’t count that. Was that, was that under 10 words?

FK: [laughs] Fans…who…get…joy…out…of…denying…other…fans…things…it was exactly 10 words!

ELM: Yes! That’s why they gave me an English degree!

FK: Because you can count words. Well, I’m really excited to talk to Miranda. [ELM laughing] But before we do that, we should talk about some stuff that is relevant to the last podcast.

ELM: Yes. Some stuff. We got some stuff to talk about.

FK: Some listener mail. It’s not just stuff, it’s listener mail.

ELM: All right. So if you did not listen to the last episode, or if you’ve been living under a probably very chill rock for the last six weeks, we talked about queerbaiting last episode, mostly around the show finale. I almost said “season finale,” but there are no more seasons of Supernatural.

We got a bunch of responses. A few of them I think were less about Supernatural and more about broader topics, so we’re gonna save those probably for our next AMA episode, but there were a few that were very specific to Supernatural, so we thought we should read them here while the constant canonicity of—Dess-tiel, as I said 9,000 times in the episode. I do know it’s Dee-stiel. It’s just, it’s just, you know when you just read a word and you never hear it out loud? You know. You know.

FK: I am the poster child of doing this, so yes.

ELM: That is you! That’s a Flourishism. So.

FK: Yeah. So for once it’s not me. OK. Shall I read the first of these letters?

ELM: Please do.

FK: OK. This one is from MissYuka.

“Hey there, just a quick reply to the listener mail from last episode that asked about the demographics of Supernatural viewers. In a recent episode of The Hollywood Reporter’s podcast they had the president of the CW, Mark Pedowitz, on to discuss Supernatural ending and he mentioned that the audience breakdown was 50/50.

“Now, after my initial reaction of ‘this sounds fake but he’s the president of the CW so I don’t know,’ I decided to check out the Supernatural subreddit and boy, if you were looking for the straight guy opinion on this show, there it is. (I looked though some of the posts marked ‘controversial’ from the past month and it gave me a headache. Would not recommend.) So there you go, the men exist and apparently they’re on Reddit. Sharing some awful opinions.

“(And yes, disclaimer that obviously Reddit is anonymous and I’m sure it's not 100% straight men on there and I'm obviously being a bit facetious.)

“Anyway, here’s a link to the podcast if you wanna check it out,” and we’ll put the link in the show notes.

“Love the show and happy ‘2020 is almost over,’ MissYuka.”

ELM: Thank you very much, MissYuka. This is very interesting and I mean, I, you know—obviously I am extremely interested in where the president of the CW got those numbers, like, how are those being calculated, you know? With any of these—are you gonna tell me it’s Nielsen ratings?

FK: I was just gonna say yeah, generally I think that the ratings that we see are not as—the information and ratings we see are not as complete as the ratings and information that people at TV networks get.

ELM: I understand that. I also, but I always do wonder with these things—and this isn’t just about Supernatural—but when you think about how many people are pirating things, what is the actual? It’s the real, it’s very very hard to actually measure this stuff, right? So it’s like…

FK: Oh, yeah. Incredibly hard. And I mean, the Nielsen ratings are like, a small sample of the population, and they don’t count piracy, and yeah, exactly.

ELM: Plus, as everyone who listens to the podcast knows, the one week when I was a—what is it, a rotating Nielsen family or whatever? You remember this, right?

FK: Oh yeah.

ELM: Not like we had the box in our home, but we had the one week where we got to be one of the like—you know, some people do it for short term and some people wrote it for long term.

FK: Right, and you wrote a diary and you juiced it to keep Buffy on the air.

ELM: False! Obviously I was actually watching Buffy, but I felt like because Buffy was on the WB…

FK: Oh, right.

ELM: Now the CW, I felt like to further enhance Buffy, I should say that I also watched Dawson’s Creek, which I didn’t even like very much. So you’re welcome everyone, that’s why it stayed on the air.

FK: OK. Right. Right. Well, in any case, I don’t find it hard to believe this number at all, even though it has such a big popular non-male-led fandom, because I think there’s a lot of television out there—there’s a lot of television viewing out there—that is not documented on the internet, even on Reddit. So even if you didn’t find the straight men on Reddit, I would still probably believe it, because I would believe that they were just, you know, dudes who watch TV and don’t talk about it on the internet. Of whom there are a lot.

ELM: Yeah, it’s a very interesting kind of question of audiences versus fans versus fandom and where those lines get drawn, and obviously as long as people are watching it that counts for something. But it does effect how conversations get shaped and who speaks in various conversations. So.

FK: Totally.

ELM: Interesting.

FK: Thank you very much, MissYuka. Elizabeth, do you wanna read the next one?

ELM: I sure do! OK, we got this one shortly after we released the episode. The subject line is “More thoughts on Supernatural and queerbaiting!” from Amanda.

“Hi Elizabeth and Flourish! Thanks for your recent episode on queerbaiting. Your take on the post-finale Supernatural drama was pretty spot on. I also wanted to offer an additional perspective because I walked away from the finale feeling baited too, but not just because of a ship. I apologize for such a long message but I have so many thinky thoughts!

“To give you some quick context, I started watching the show in season 10 and became a ‘fandom’ fan—attending conventions, etc. So I’m not just a casual fan. However, I would consider myself a casual shipper in the sense that I didn’t feel super emotionally invested in whether Dean/Cas went canon or not. It would have been cool for the story but I was good either way. Yet, I still walked away from the finale feeling like I was on the receiving end of the world’s worst bait and switch.

“Throughout Supernatural’s run, fans and fandom had been written into the narrative, and not just in a meta, breaking the fourth wall kind of way. There was an episode about fan conventions, a recurring ‘fan’ character named Becky, and an episode titled ‘Fan Fiction’ for crying out. So I think it’s safe to say fans felt as if they had become part of the story.

“Also, the show had developed a theme of ‘found family’ over the years, leaning heavily on the early seasons line of ‘family don’t end in blood.’ Over the years the show seemed to have heard fans’ requests for more representation. So supporting characters over the years not only became more diverse but also came to represent Sam and Dean’s ‘found family.’ In turn, because of the improved representation, fans came to see themselves in that found family. I think fans also saw themselves in Sam and Dean, wrestling with themes of fate vs destiny, finding purpose, overcoming trauma and grief.

“So with the meta nature of the show and it’s found family themes, many fans after the finale are saying they, as fans, felt erased from the show, not just the characters. And it felt intentional. I think many of us went into the finale feeling like we were all in this together—writers, creators, fans, the characters, the story. But in the end it felt like that last episode was a middle finger saying ‘this was always the creators’ show, it was never about you.’ Whether that was intentional or just a byproduct of capitalism and homophobia, who knows. But I do know even non-shipper fans walked away from the finale feeling used and manipulated, strung along for money, ratings, and attention.

“The most heartbreaking part is to read fans’ posts as they process their feelings in real time. Now that we’re two weeks out from the finale, I read more versions of ‘I just feel so stupid,’ like they’d fallen for a manipulation and they blame themselves. I have to say it’s left me personally very disillusioned with fandom. This is the only fandom I’ve ever participated in so maybe I’m naive. But it’s left me hesitant to get emotionally invested in another fandom.

“It certainly brings up a lot of questions in terms of the future relationship creators have with their fans. While I don’t think fans should dictate what creators create, I do think the fan/creator relationship has evolved to be more reciprocal in nature. And if that reciprocal relationship is going to continue, then should the end product be treated with more care?

“Anyway, I will probably be screaming into the void over that shitty final episode for the rest of my days so I thought why not pass on my thoughts to Elizabeth and Flourish! Thanks for your hard work on all things fandom! Amanda.”

FK: That’s a really interesting letter, and I really appreciated getting it. Thank you, Amanda. It was interesting because, you know, what you were saying immediately made sense to me, as somebody who has been watching Supernatural—even though I didn’t feel that way, probably because I was not involved in the fandom, like, in a super-active way.

That makes perfect sense as far as why the last episode in particular, which pretty much shuts out everybody except for Sam and Dean and removes all of those sort of supporting characters that people identify with and care about and so on—you know, it makes sense that that would feel like that. And it hadn’t occurred to me before, probably because most of the reactions I saw were so related to shipping.

ELM: So for this show in particular it is interesting to think—I know, through my sheer osmosis, I have seen a lot of commentary about how they wanted to have a big, large-cast kind of final hurrah, and they had to really limit who could be involved in the few final episodes because of the pandemic. Which is like…to me then, I don’t actually know the details of well, why not just delay it? Say we can’t—you know, some of this stuff that’s still getting shot in the kind of half-assed…not half-assed, but half-functionality sort of way, you know what I mean. Full-assed, but [laughs] very limited…

FK: I would guess it would be really hard because the show is ending, the actors have other commitments and so on. I’m sure…

ELM: They have other things to do, yeah.

FK: Especially since we know that the actors are starring in other things next, you know what I mean? It’s not like they have forever to go back, and it’s not like they can do it without Sam and Dean. So.

ELM: So one thing this immediately made me think of when I read it—which I really appreciated, I also really appreciated this letter, it was very thoughtful—and obviously, as you were talking with us, I’ve heard and read so much about Supernatural fandom and the kind of meta-narratives about the fans within the show that it actually winds up making somewhat of a different beast than even…we brought up Sherlock a lot in the last episode, and obviously Sherlock has a meta-commentary about fans as well, but not to the level of like, an episode called “Fan Fiction” and a recurring fangirl character and a villain that is a writer of the world and all this. That’s extremely meta, right?

FK: Yeah, and I think also with Supernatural, people really hated the way they wrote fans in—I mean, not all people, but a lot of people within the fandom—really hated the way they wrote fans in at first, and the writers seemed to learn, you know what I mean?

ELM: Right.

FK: And they changed the way they portrayed fans. So I think that probably has to, that’s one of the reasons I think people are so attached to that aspect of the show. Because like, it was one of those cases where people complained about it and it changed, you know?

ELM: Yeah, whereas the depiction of fans was brief and negative in Sherlock, and no change ever happened, and that was that. But the letter also did immediately make me think of the reaction to the Game of Thrones finale, and in a way that kind of was refreshing, because I think in the last episode—while we talked a bit about, you know…it’s not like it’s just about the, like, there’s no “just” about the ship, or “just” about queer representation on an individual level, or on a pairing level, or something like that. Those things aren’t, I don’t wanna say anything that’s like “Oh, you should care about the—that’s just one of your little things that you’re interested in,” right. That’s not at all what I’m saying.

But it is interesting to think about Game of Thrones and the reaction to that because that does take away—you find some similar reactions, but it, there was no potential queer endgame ship there.

FK: No.

ELM: This was just people being extremely disappointed with some bad writing, as far as I’ve also learned through osmosis. Right?

FK: Yeah, I think that that’s fair. In fact, if anything—yeah. Absolutely. [ELM laughs] Many ships happened in that show, not all of them the way that people wanted them to, not all of them very well.

ELM: Right. But it didn’t feel like—obviously I think there are interesting things to say about, well, what about a show where a huge portion of the fans are hoping for a canon ship of any kind to emerge out of a finale, versus people who want a non-romantic-related satisfying ending like they wanted with Game of Thrones. And you know, there were so many people feeling betrayed by that, and feeling like they had made a pact with the writers that the writers wouldn’t do a bad job. And the writers blew it. Right? You know?

And it kinda made me think at the time—what is the pact that these writers have with you? Right? You see the same thing, I’ve been thinking a lot about the reaction to the last Star Wars movie too, right? And the kind of, this sub-level of the…not conspiracy theory even, but the like, there was some better cut of this that would make it not a piece of garbage, right?

FK: There must be something good. It’s not possible that people just produced a bad thing.

ELM: Right!

FK: There must be some reason why they produced the bad thing beyond just: it’s hard to make, it’s hard to make a movie! It’s hard to make an ending of a TV show! A lot of them suck, you know? Sometimes the one you love sucks.

ELM: Right, right. And I mean, I guess the like, the pandemic limiting who could be in this, and betraying the themes that fans felt had been built up over 15 seasons, is part of it too. Because as you’ve really illuminated for me, there’s so many times that what we read as mediocre or bad writing decisions are the result of external factors, whether it is an actor getting a different job or an actor just not being available for a couple of weeks, you know, so they can’t just be in this thing, so you have to write around it in a hackish way or whatever. You know? And it’s like—I don’t know.

I keep going back to this thread that you wrote that we should link to in the show notes, a couple days ago, about this idea of the characters having a true version of themselves and people not allowing them to be true and to speak their truth. And it’s just kind of like—when you get into that mindset, which I feel like a lot of fans are doing, then it’s really hard to keep in perspective the fact that this is like, authored by humans. I don’t think our letter-writer’s doing this at all. I think that she’s acknowledging that, you know.

FK: Yeah yeah yeah. This is authored by humans and that it stinks when they don’t, yeah.

ELM: Yeah. Whereas I think a lot of people are doing that where it’s like, there’s a better version there, and you know—it sucks to think, “Oh, they made bad writing decisions,” or “Oh, they weren’t available to do this thing, and so it came out, they produced something bad.” But like, you know what I mean?

FK: Oh God, do I ever know what—you know, you just saying that made me realize something that I had literally never put together in my head before.

ELM: Oh wow.

FK: Which is: I have talked a million times about how I, the first time I kinda broke up with Harry Potter, being over the last book not fulfilling the themes that I thought I had seen the entire time. And in a certain way, right, I wasn’t a conspiracy theorist and it wasn’t about shipping or anything, but I believed that I had a reading of this book that coincided with what the author was trying to do. And to me, I had it in my head: yeah, this perfect vision of what the author was trying to do, and I was expecting it to be fulfilled. And when it wasn’t, that really sucked, you know what I mean?

ELM: Yeah.

FK: And I can totally imagine being in a situation where I was like—if it wasn’t in that, because in that case, it’s so clear: J. K. Rowling wrote it, no one was editing her at that point, there’s nothing to hide behind.

ELM: Absolutely not, nope.

FK: She sure wrote that thing, right? But I can imagine that if I was in a situation where there was someone to blame, that I might well have been like, “Oh, someone edited her and made it suck. Someone—”

ELM: Yeah.

FK: “There were pressures on her. Clearly, because she could not have come up with this shitty thing.” You know? And I guess I’m lucky, then, that that was my experience of it, because I think that putting those things together gives me a new appreciation for the emotional place people must be in. Because I really, you know, that was a really hard thing and I didn’t have anything to sort of blame. But if I did have something to blame, I definitely would have gone for it.

ELM: Yeah. I mean, I think that books, in that way, make it a lot simpler, because it’s, you know—I don’t know why, maybe it’s because they just announced 150,000 new Star Wars projects coming out, but like—you know, thinking of this kind of idea of who’s the bad guy here? There has to be. And you’re seeing some of the same conversations with Supernatural. There are, “the people closer to it, making it, have the stifled true artistic vision, and the corporate suits,” you know. So J. J. Abrams had some secret great version, and then Kathleen Kennedy—the monster—and the corporate suits stamped it out, right?

And this kind of idea of wanting to pit different parties against each other when in reality—we have no idea of how things pan out in terms of what different decisions get made there, and…it’s hard to look at these things…I’m not saying everyone is a conspiracy theorist here, but there is even—wholly outside of the conspiracy theory stuff, there are people who are eager to assign specific blame and specific credit for creative decisions that I think that, unless you are the director of the thing, or the writer of the thing, you may, there’s no way you’re gonna know exactly how that broke down, right?

FK: Yeah! And there’s huge numbers of people that you don’t know exist, right? So people tend to try and pin things to people who they know exist, right, because obviously—you know, unknown unknowns. You’re not gonna, right? But there’s an entire Story Group at Lucasfilm, you know what I mean? There’s all these people who work there who work within story issues across all the franchise, and you don’t know who they are.

ELM: But I”ll tell you one thing I do know, Flourish, is Kathleen Kennedy just wanted to come in and make it BAD!

FK: Right, exactly! And similarly you’ll have people on, you know, again—you have people, whoever decides to talk about things who’s on the crew for a show, right? [ELM laughs] And suddenly they become the guru of all things!

ELM: Good subtweet!

FK: Even if they have no relationship to this—who knows, right? Because you know them, and you know that they’re associated, so suddenly they become sort of the mouthpiece in your head.

ELM: So this is why, I think in wrapping up—to wrap this up, like, to me, I think this kind of—this very production, this eye on production, trying to parse what happened that led to a thing, to me is very—it’s like a lose/lose kind of scenario. Because in the end, to me, just look at what you got, you know? Which actually, I think, brings it back to our letter-writer here, because she’s looking at what they got, and she’s like, “They set up these themes and then they were like, bleh.” You know?

FK: Right!

ELM: [laughing] Which, like, I think—I bring up Game of Thrones as a parallel, and as far as I understand it, and this is also from the outside looking in, it wasn’t necessarily a betrayal of themes as much some bad story decisions that are just like, “Oh,” you know?

FK: Yeah, and a bunch of stuff crushed into a season—and I mean, yeah!

ELM: So like, there’s two different ways to go about it: you can try to parse “Why exactly did this happen?” Or you can say “All right, I think that what happened is bad and I’m gonna explain why. I’m gonna analyze that. And I’m gonna say, here are the themes that they set up before, and they failed to see these through to a final conclusion.”

FK: Right, and then write some fix-it fic. [laughs]

ELM: I mean, yeah. Or, or just critique it! Like, you know. I know there’s been a lot of pushback to Misha Collins’s I thought very open-ended positive creator-side statement of, “We’re opening this wide up for you to write all the fic that you want.” Like, honestly, that’s kind of an awesome statement for someone on the creator side to say, just in an open-ended way without judgment—just “Take these characters, they’re yours now, we’re done.”

FK: Yeah.

ELM: And I understand why people got upset with that, because they were like “Well, why do we always have to do the work?” But it’s like… [sighs] You know, I mean, I obviously understand all the different factors involved in this. But like—I mean, obviously it’s me, so in the end I’m gonna be like, “Your fic is gonna be better than anything they coulda done anyway, because that’s fanfiction, so.”

FK: All right. I think that that is a good button to end on.

ELM: Yeah.

FK: Elizabeth says your fic is gonna be better than anything anyone can write.

ELM: I’m just saying.

FK: Before we call Miranda, we should do two things. We need to have a little break, but we also should talk to people about Patreon.

ELM: OK. We’ll do—you wanna do the break and then Patreon or Patreon and then the break?

FK: Patreon and then the break. Let’s get it over with.

ELM: So, very quickly, patreon.com/fansplaining—that is how we pay for the podcast, through the generous support of listeners and readers like you. Anyone who isn’t familiar with Patreon at this point, you pledge on a monthly basis, as little as $1 a month, as much as—realistically $10 a month is where the top of our pledges are. But you could go higher if the spirit moves you!

FK: Sky’s the limit!

ELM: Yeah, that’s right! [laughing] All your dollars! Or euros, or pounds sterling, because we take other currencies through patreon.com. But our most popular tier is $3 a month, which gives you access to all our special episodes. There are more than 20 at this point. We’ve talked about our own fanfiction reading and writing practices, we did a series called Tropefest where we talked about the Trapped Together trope, or Enemies-to-Lovers, and then we talked about a whole bunch of different media properties, which is something we don’t often do on the podcast. So kinda critical reactions to things like Schitt’s Creek or The Favourite or The Good Place. I can’t remember the probably 15 other things we talked about, but.

FK: There are a lot of them.

ELM: Yes. So there’s that. $5 a month gets you your name in the credits and also an extremely cute fan-shaped enamel pin, and $10 a month—we still have some, right?

FK: We do!

ELM: You get a tiny zine and all future tiny zines. The current tiny zine we have copies of is my fandom story about kind of learning that other people wrote fanfiction via an upsetting story about Giles that I read when I was 14 in 1999. It’s illustrated by Maia Kobabe, and it is literally the cutest thing I’ve ever seen in my entire life.

FK: It is. But. But! Totally understand if folks can’t support us monetarily, there are other ways you can support us: by following us on your favorite podcatcher or iTunes or whatever, by leaving us a review, by telling your friends about us, and also by writing in to fansplaining at gmail dot com, or calling in to 1-401-526-FANS, or sending us a message on any of the social medias. We are generally speaking fansplaining. We aren’t on TikTok, don’t try it.

ELM: You can’t just say “any” now. TikTok: a thing.

FK: You’re right, we can’t say just any.

ELM: We’ve also never been on Snapchat or LinkedIn.

FK: Well, anyway, on many of the social medias we are fansplaining. You can find us there. Send us your thoughts, your questions, your letters like these, that were so great!

ELM: OK, break time and then Miranda time!

FK: Let’s do it.

[Interstitial music]

FK: All right, I think it’s time to welcome Miranda to the podcast! Welcome, Miranda!

Miranda Ruth Larsen: Hello! Thank you for having me.

ELM: Thank you so much for coming on. I, I was gonna be like, “I’ve been a fan of yours for a long time,” and then I felt cheesy on Fansplaining, but it’s true!

ML: Aw!

ELM: I have been.

ML: I still don’t know how to respond to that, so. [laughs] Thank you.

FK: Well we’re really happy you decided to come on.

ML: Yes, thank you for having me.

ELM: So should we, we usually start with guests by asking them about their fandom origin story, and with like, people who professionally work studying fans or working on fans also, we ask how that intersects with their professional careers. Cause often they’re intertwined. So you don’t have to give us every single detail, but the rough outline of it.,

ML: Yeah. As a kid, I definitely had that kind of focus, of “I am really into this thing.” For a long time it was Egyptian mythology. [laughs] And Greek myth. I would read any possible thing about those.

FK: Classic nerd-kid freak-out things.

ML: Exactly!

FK: I feel ya.

ML: Exactly! And then when I was about 10 was the hit, like, the big wave in the U.S. for Pokémon and Yu-Gi-Oh! And that realy sent me down the anime path. And the anime path is how I discovered that I was really interested in Japanese popular music and Japanese language.

So I always tell the story when people ask me, like, “How did you end up at the University of Tokyo? Why can you speak Japanese? What interested you in this?” And they expect someone to say, “Oh, I really am interested in geisha,” or “I love samurai” or something. For me, it was that I was reading a fanfic for Gundam Wing and the author’s comments said, “You should check out this track by this Japanese singer called Gakuto, it’s perfect for this.”

And that was in the day when YouTube didn’t work if you were like me and had dial-up, so I think I downloaded it and it took me about four to six hours. I watched the video once, and I said “This man is beautiful and I need to know how to speak his language and I need to move to Japan.”

FK: [laughing] I think we must be the same age, because I just had a full-body flashback to that period of time.

ML: Oh, correct.

FK: When people—I was never a Gakuto guy, but people I know really were. And I remember the obsession in them.

ML: Yeah, I still am. It hasn’t gone away. I luckily, right before the coronavirus hit in Tokyo I went to his concert, so—every time I go I put a letter in the fanmail box, it’s like, “I’m at the University of Tokyo because I saw you on the internet back in the day!” [laughs] “Thank you!”

But that’s really where it started for me, for liking things from Japan, and then I branched out. I started listening to like, C-pop and Mandopop, and then eventually got to K-pop when I was in college. I really turned to K-pop when I was getting my film degree at UCLA, because it was more accessible in Los Angeles, compared to where I had grown up. But I, no, I never expected that I would end up being like, a K-pop scholar [laughs] for people, for people at all.

ELM: Is that how you would define yourself now?

ML: I still like to say that I mostly identify as a cultural studies and fan studies scholar. Of course a lot of people still believe that identifying as a fan studies scholar is taboo and you shouldn’t do that—at least if you want a job. [laughs] Supposedly. But I usually say media studies more broadly and cultural studies, with a focus on gender. So it doesn’t matter if I’m looking at K-pop or anime or horror film, like, those are my three big areas—I’m always caring about, you know, gender and then the transcultural experience.

ELM: All right, well, it’s 2020. I think we should probably start with K-pop, because I hear that’s a pretty trendy topic to talk about in 2020, so… No, seriously, like, OK. It’s a very, probably a very weird year to you, someone who has studied K-pop for many years. This has been a, you know—I think for the last few years in our Year in Review we’ve talked about the kind of rise in K-pop amongst Western fans, but this really feels like a huge sea change has happened in the last 12 months to me. Is that how it looks from your perspective?

ML: Well, it’s hard for me to comment on that, because the other thing that’s happened is in the last 12 months I’ve transitioned from living in Japan to coming back to the U.S. So my relationship with not only the K-pop industry and fan interactions but just the availability of flows of comments on SNS based on time zone is not a little different.

ELM: Fascinating.

ML: Obviously there was a huge interest, a spike in interest, in June and July, with the relationship between K-pop fan power—as it was articulated in many, many an article—and BLM, and also political activism. So for a few months, I was essentially fielding at least three or four emails every day from someone who wanted to talk to me or do a podcast or pick my brain about [laughs] what is this and why is this happening.

And it was very strange for me, especially because previously I would be in Japan almost all of the year, I would travel back only two times a year: once for SCMS, the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, the annual conference, and then also in the summer, because K-Con, which is the biggest Korean culture, life, merchandise, everything convention, would invite me as a special guest. So normally the K-Con experience was my big exposure to, “Oh, this is how American fans are interacting with this phenomenon,” and now people want me to comment as an expert on the American fan side—but a lot of what I see in the American fan side, I don’t have many rosy things to say.

ELM: Do you wanna say them? [all laugh]

ML: Yeah! I think that there’s, there’s something… [sighs] There’s something very interesting with, so you used the term “Western,” and I usually try and avoid, because first of all—going to school at the University of Tokyo and being in a room full of international students and someone says “those Westerners” was a really enlightening experience for me. But I’ve been using “Anglophone” a lot, because especially the K-pop activity you see on Twitter and also on Instagram—for me it is something that is attached to the English language. Not necessarily native English speakers, but the English language and people using English.

And it’s a really entitled version of K-pop fandom that is ironically divorced from physical closeness. So physical intimacy. So it’s almost as if the closer you are, the less obvious some of these behaviors are. Of course, there are—they call them like “sasaeng,” so, very dangerous types of fans, in Korea, who are harassing idols, who are harassing other fans in person and online. Of course that exists. Of course it exists in Japan too.

But in the U.S., where there’s almost no chance of interaction aside from an occasional tour or an appearance at K-Con, it seems that there’s two results from that: one are fans who are absolutely obsessed with metric culture. So, streaming, numbers, charting and awards, as fandom. And two, a lot of the toxic behavior you see in terms of harassment and doxxing, especially on Twitter.

FK: It’s really interesting that you—I mean, obviously anybody who uses the internet knows that the internet is pretty segregated depending on sort of what—even just what character system you’re using, maybe is the most. But it’s interesting to me because I guess I had always had an idea that there was a little more crossover or free-flowing, you know. Maybe just from my experience of knowing other people who had, like, been really into anime and learned Japanese or whatever, I guess I had some assumption that there would be that kind of—you know, not perfect connection between Anglophone and other—I guess really other character-set-using fans. [laughs] But it sounds like they’re very divorced from each other in your opinion.

ML: Yeah, they’re very divorced from each other and I think part of what started this was, in the beginning, if you wanted to be part of an official fan club—which is a very big thing for K-pop—a few years ago you couldn’t do that without illegally, you know, renting a mailbox in Korea or in Japan. You could not do that as a person outside of a certain sphere. So you would join a fansite, right? Which is very similar to what we might have seen in anime fandom, maybe about 10 years ago—10, 15, oh God, I’m dating myself. [laughter] It’s very similar.

But now there are official international—and often times the groups have two different versions with different benefits, with different, you know, bonuses that you get sent to you. So from the structural level, it’s saying that there is a divide, usually between—we would abbreviate it as like, K-fans and I-fans, Korean fans and international fans. Then, even more so with Japan, because Japan is its own protectorate site, and they tend to get their own exclusive content, even different from the Korean fans. And I think that’s, that really set up part of this.

And then add on top of it—at least for the anime boom that we’re talking about, there had already been sort of a building in terms of Japanese technology and video games that Japanese language programs were sort of robust in higher education. That really didn’t happen in the same way for Korean. So this interest in K-pop has led to almost a ridiculous boom in people wanting Korean language courses. So I think that’s another thing, is it’s a smaller community of able and willing translators when it started. That’s not the problem now, but when the crossover began, that was definitely a big difference between the two.

ELM: In your—maybe it’s impossible for you to answer this, but of the Anglophone fans you see very very active now, are you able to estimate what percentage have come, I would say, like, in this kind of sea-change of the last couple of years? Cause I know that there were plenty of Anglophone fans into K-pop for years and years, right?

But I’m just curious, partly because you like, cited the metrics culture as something that Anglophone fans are very engaged in, and I have just been kind of wondering from my very distant perch here about metrics culture, in terms of like, seeing how that works within Chinese-language spaces, right, and I’m curious how that works within Korean-language spaces, and of course if you’re describing that as something that is very popular in the international spaces—are these things happening independently, or are they kind of cross-culturally coming from one place to another?

Does that make sense? That was a lot of questions, I’m sorry. I had like seven questions.

ML: Well, I think—to answer your first question: yes.

ELM: [laughs] Yeah, do all seven!

ML: K-pop fandom, [laughing] K-pop fandom is not a new thing. K-pop fandom existed before BTS, regardless of what many people might want you to say or believe. K-pop fandom has this really interesting tie to two things: one being the diasporic community of Korean-Americans, if we’re talking about the U.S. specifically—but especially North America, so also Korean Canadians. And then, the second is K-pop’s investment in things like YouTube, in more accessibility.

So whenever anyone asks me “Why did J-pop fail?”— [laughs] “Fail.” Compared to K-pop. It has to do with these protectionist practices. K-pop was always designed with an outward look. As I rant about anywhere, K-pop’s main influence is Black American music! It was always created with an outward market idea, compared to J-pop, which is ironically mostly written by people from Iceland and Nordic countries.

FK: That’s so funny. It makes me think of—so, I have a black belt in taekwondo, and it makes me think about taekwondo, in terms of like, all of the different martial arts. Out of all of those I would say that taekwondo is the one that is most made for export. It’s a conscious cultural thing—at least in my experience it has been.

ML: Yeah, and there’s lots of discussion about how much is coming from the top down, how much is the more grass-roots fan networks that we’re used to talking about—about people offering resources to each other, not just in the sense of files, but how to navigate certain websites, how to access maybe local import/export businesses so that way they could get albums. But there’s definitely a huge difference between…

When I first encountered K-pop I was in my Japanese class in Syracuse University for my B.A., and I had a friend who showed me a video for Super Junior and said “Look! You would like these guys.” And I said, “There’s way too many of them. I can’t keep track. They dance really well and I like it, but I don’t know.” And then I found RAIN, the male solo artist RAIN. And he was basically [laughs] you know, the father of moving K-pop through East Asia into Southeast Asia, and then globally, you know. He was in multiple Hollywood movies, I went to see the Wachowskis’ Ninja Assassin starring him—problematically playing a Japanese guy, but still. Multiple times! And I remember just sitting in the theater screaming. Luckily it was only me and my friend. [all laugh] We were just screaming, saying “There’s RAIN!” and, you know, “He’s gorgeous!” and “Oh my God!” But we never thought to ourselves, “We need to go and see this movie 15 times to help him.”

And that’s the ethos of the metric culture now. It’s not just “I wanna have this thing because it means something to me,” “I wanna have this thing to enjoy it,” or “to share it with my friend,” it is this almost professionalization of what you see in other spaces like MMORPGs, with like, gold farming. It’s [laughs] you’re essentially doing the same type of work, of putting out there: “This is what you need to do, to watch their YouTube video this many times, to get it to count. And this is how many accounts you need to vote.” And that’s not my type of fandom. [laughs] And that difference, especially in the Anglophone, makes for a lot of frustration and a lot of…I don’t want to say that it’s inherently generational, but it does have to do with like, a generational sense of access.

ELM: Wait, can you expand on that? And can I also just say too that I have noticed, I have noticed a lot of people I know from Anglophone TV and film media fandom over the last, you know—I know them from several years, like, several fandoms back, right? Joining K-pop fandom, specifically BTS fandom, within the last two years, and they are not young, and they are getting fully on board the metrics train. In a way that I find very fascinating, and I’ve kind of, just for context—ribbed on? Is that the expression?

FK: Ribbed, or riffed on?

ELM: Dunked on?

FK: Dunked…

ELM: On Flourish—

FK: OH.

ELM: —for engaging in a little bit of this around Harry Styles, like, awhile ago, you know? Just—so, so it’s interesting cause it’s like, that’s why I’m curious about the generational thing too, because is it when people just show up within these music fandoms…

FK: Can I just say in my defense, by the way?

ELM: Oh, yeah, all right!

FK: When it’s sort of the water that people are swimming in, right, you may or may not care very much yourself—speaking just for my own self and not for any K-pop fandom—but like, I don’t find that to be so exciting, but when everybody that you know who’s talking about this artist is also doing it, it feels like sort of the thing that you do, and then you just sort of do it. Anyway, go on, Miranda, tell me about this in an actual studied way.

ELM: You had to defend yourself. Go ahead!

FK: Explain this phenomenon that I did! [laughs]

ML: Yeah, I don’t think that it’s generational in the sense of “somebody under the age of 30 does this and someone over the age of 30 does this,” although there is a huge amount of ageism in Anglophone K-pop fandom. You will see a lot of tweets by younger people, and by “younger” I mean “under 20,” who seem to think that if you are over the age of 21 you have no business in this.

ELM: You should just shrivel up and die at that point.

ML: Which is—yeah! Your life is over.

ELM: That’s it! That’s it.

ML: So there is obviously an ageism problem, so that exists. But no, I mean “generational” in terms of the K-pop that we’re dealing with. So when I was talking about when I encountered K-pop, we usually call this Korean wave, hallyu, 1.0. That means at the time, K-pop was mostly secondary to K-drama as the main export for the Korean wave. So it existed, you could get it, but it required a lot of work.

That’s very different than now. We’re in Korean wave 2.0. And in 2.0, K-pop is the forefront. You can get it on iTunes. It takes two or three mouseclicks and you have it. You can go—just today, my family was talking about, they were looking for gifts at Barnes & Noble, and there’s a K-pop section, and it’s all BTS. So of course my mother had to report this to me in order to share the fury. And that’s, that’s the difference. It’s access and accessibility.

This happens in other fandoms too. It’s the same thing as anime. It depends on where you started in anime fandom for—did you watch an underground, terrible, VHS at a con? Did you download it, you know, piece by piece? Did you watch it in fraction bits on YouTube? Or is it like now where I can go to Hulu and watch 15 series without even thinking about it? It has to do with the technological side of it, I think, more than anything. That’s the difference.

FK: That’s interesting too, because it’s not as though that’s something—I mean obviously it’s very specific when it’s something that’s transcultural or that’s a cultural import to your country, but it’s not as though other fandoms don’t also sort of have those generational waves piece, right? Like, Star Trek fandom or Star Wars fandom or anything else. Right? And you see huge conflicts between people, because I guess different periods appeal on different levels and then you get people who really don’t have the same interests within what’s supposedly all one fandom.

ML: Oh yeah. I mean, that’s the thing. That’s another thing that I like to point out to people, is: we say “K-pop fandom,” but it’s really “K-pop fandoms.” It’s so many different iterations of people and what they’re interested in, how they want to express that interest, how they wanna interact with other fans, and how they wanna interact with the idols. I think fandom, for some people, has just become an excuse for behavior that is not OK. [laughs] In the same way that you might see it in any other fandom. But especially in K-pop fandom.

This is why I tend to really be against the idea of—I never use the word “stan.” To me, “stan” is the marker of the more toxic engagement that I don’t want to involve myself with, and a lot of times that metric culture—I identify that with standom as opposed to fandom.

ELM: Do you also within that—so the other, that is also how I define “standom,” alongside this sort of defense culture, the object of fandom, the—I almost said the “idol,” but this obviously goes beyond, all sorts of fandoms that don’t use the term “idol,” right. The celeb or whatever, right. You protect them at all costs.

ML: Oh, I mean, this is ancient. This is auteur theory in film. [laughter] This is the idea that the people—I mean, I love horror. Rosemary’s Baby is one of the most important films in the horror genre. I cannot divorce that from what Roman Polanski has done with his personal life and the crimes he has committed. You will see this in film studies going back to the beginning of cinema: it’s nothing special in terms of K-pop.

I think the fact that K-pop fandom, like many other fandoms now, have such a significant online presence, and for many people the online world is the entirety of their fandom experience—that’s what leads to the metric culture, the defense of “they can do no wrong,” “he didn’t mean it,” “it’s not cultural appropriation, they’re just appreciating you,” any of those types of defenses that you might end up hearing—it really is because, I think, the technology has changed how we engage with these things.

ELM: Do you think that the pandemic, with this kind of physical disconnect, has exacerbated this this year?

ML: Absolutely, in terms of the K-pop industry, it’s taken a huge toll on not only revenue streams but yeah—people have a lot of free time. [laughter] There’s a lot of people stuck at home, or they have the ability now to be multitasking, right, to be monitoring chart data or major fan update accounts, and in some ways I think it’s led to some very wonderful fan output, in terms of transformative works, connecting for charity. But you can’t ignore the other side of it at all. So.

ELM: Yeah, yeah.

FK: It’s really interesting saying like—there’s really good things and really bad things. Because I feel like one of the things with, especially everything that happened around Black Lives Matter, was that suddenly there was this narrative that had to be, like, expressed somehow in the U.S. press, and it was either “The K-pop people are angels and they are going to save us all,” or “The K-pop people are devils and they’re actually terrible in every possible way,” and I kind of feel like neither of those things can possibly be completely true, but it gets really hard to sort out when you’re not within the fandom itself, and you’re like—I mean, obviously you know people and they say things and you’re like “ah, I trust you.” But it’s very strange. I’m interested in your take on this particular narrative, because I feel like I’ve heard it from so many different people, and—I don’t know, I still don’t know what to make of it.

ML: I was definitely one of those voices that was leaning more towards the negative side, just in terms of saying that context matters. So some of the behaviors or some of the actions that people took were obviously with the right intention and led to‚ I know anything that involves people laughing at Trump, OK, I’m good with that. But at the same time, as I said, and I did multiple interviews—it was the same skill-set, it was the same organizational power, that many of these fans use to harass and dox people. It’s the same power that they use to harass idols they do not like. Or their own idols when they feel betrayed, because that does happen from time to time.

So I was extremely wary of the “angel,” you know, “K-pop fans are part of the Resistance,” “K-pop fans are the new—” someone coded them as the new Anonymous? And... [laughter] That also was not…what I felt really worked? It also treated K-pop fans as a monolith. And they’re not. It was extremely difficult to see so many celebratory texts, when at the very same time, you would see accounts who were saying “we need to do this for BLM,” and two months ago they were calling someone the N-word. You know? And three months later, they’re doing it again! It is just, for many cases, it’s for attention. And it makes me very sad, because I of course want people to—anytime that fandom leads someone into activism, I think it’s a really interesting, not only a personal experience, but as a fan studies scholar, to check that out. But it for me—I was the one raising the flag of alarm going “Stop it. Stop feeding them. You don’t know what’s coming, because it’s going to get bad.”

ELM: I’m curious to know your opinion generally about—when I think about K-pop and I think about that period of the year, I also think about the media in general and the way that K-pop engages with the media. And that was interesting, that whole period, because it was like, so many journalists who never—they had to spend like two-thirds of the article explaining what K-pop was and what fans were and what the internet was or whatever, and it was like “All right, guys, maybe just skip it.” I’ve had to write a lot of 101 kind of parts of my journalism about fandom, I get it, but like…

But I’ve seen journalists in the last six months, like, change stories because they’ve gotten harassed, because they weren’t nice enough—because they weren’t super nice, they were just kinda nice about various K-pop artists. I’ve tweeted mildly positive things about K-pop and gone viral and had to mute those things, and I’m just like—I don’t deserve retweets for just saying something generally nice, but… You know what I mean? That kinda thing. And so then you put journalists into this weird metrics space too, and I’m wondering what that looks like from your perspective as a not-journalist. As a scholar of this.

FK: As a person who’s been talking to a lot of journalists, right?

ELM: Yeah, absolutely, right! How does—yeah, how does that look, broadly, to you, and obviously in the context of this: journalists’ roles in these narratives.

ML: Obviously journalists have, you know, with academia there’s their own set of ethics and morals, and then also what they feel not only do they owe to represent in terms of the story, but also the people involved in the story. And I had a really varied amount of experiences with the different journalists I talked to and the different interviews that I did, and I shut down quite a few and just refused when I knew that all they wanted was the “everything is wonderful,” rosy narrative. If anybody ever emailed me and ever said “I wanna know how Army has blah,” unless it was, you know, “made fan studies harder,” I did not want to [laughing] engage—

ELM: [laughing] Classic journalist question.

ML: Yeah. I did not want to engage with it, and I would come right out and say “I am not the person you wanna talk to, because I am going to try and give you the full picture. You have this part. I have all of these other parts. And you need to talk about it.”

At the same time, journalists are doing their job, and when I see a lot of the fan reactions like you were talking about of, “they weren’t nice enough,” there’s been quite a few time when it’s “the image that you picked wasn’t flattering,” or “someone was cut out of it, so now we will end you.” And I don’t understand this, this level of entitlement and possessiveness over those idols that most likely those people haven’t met. In many ways, they are fulfilling some of the worst stereotypes that people have about fandom and about what it means to be a fan of a media property or of a celebrity, especially celebrity fandom.

And I think it caused a lot of antagonism in the journalism community, because it became very clear who was willing to write puff pieces, who was willing to write fluffy bylines, who didn’t want to talk about darker things like—why did a member from BTS sample Jim Jones, and then it went away, and it happened during the BLM thing? Oh, let’s not talk about that. You know. I was interviewed for that twice, and it vanished. Those types of things seem to keep happening.

I will say that personally, also because of the work I’ve done at K-Con where a lot of times they mix academics and journalists or just cultural commentators, it is a really different space in terms of how much antagonism they’re willing to tolerate, compared to academia, I think.

ELM: You’re saying journalists are willing to take more or less?

ML: I think in some cases it is less, and they learn very quickly that if they want to be a darling in the space, that they will only include the positive.

ELM: Yeah, that tracks. The one that sent me over the edge was—I believe it was like maybe a seven-member group, I don’t remember which group it was. And the journalist only got six of them on the record?

ML: Mm-hmm!

ELM: And—maybe you know which one I’m talking about! [laughs] And then people yelled at her for a long time and she was like, “Well, the seventh one didn’t respond to my request for comment.” And they were like, “You’re unprofessional!” It’s like, that’s not—I don’t wanna put too fine a point on it, but there is something, I think it’s like absurd to say…I’m gonna say it anyway. It feels of the Trump era to me. And I say this like, with the knowledge that like, our mayor Bill DiBlasio also feels of the Trump era, this kind of, this insistence that journalists print exactly what you want, right. Which is like—obviously celebrity journalism runs a full gamut from this kind of basically regurgitated PR piece to something that’s actually critical, right. So…

FK: Do you think that has to do with the affordances of platforms that we’ve gotten used to, though? I mean, like, when I say that, to translate from academic talk…

ELM: Yeah, use a normal word.

FK: Sorry, I can’t help it.

ELM: [pompous voice] Oh yes, I do believe it’s the affordances of platforms, Flourish. Hmm. [laughs]

FK: The way that different social media sites are, you know, the things they let you do and the things they don’t let you do. Like, the things that they make it easy to do or hard to do, right, tend to sort of—I think—drive your behavior in certain ways. So like, if you have the ability to smash a “like” button, then you’re going to start seeing the world in terms of like buttons, right? And if you have the ability to downvote something then you see it in a different way. I’m just curious if that, do you think that is true also in terms of the way that fandom exists on social media sites. Is that part of the way that, is that part of why it’s so different, do you think?

ML: Oh, absolutely. Think about how many journalists have been dealing with their employers shifting entirely to digital and no longer having a tangible newspaper for people to purchase. If the point of the newspaper is no longer for you to purchase it, to sit at home and read it and then discuss it with your family, and it’s now to read an article and share with however many people you have on your social network, it’s completely changed the scale of things. It’s also changed the focus.

I also think that there’s been a lot of cuts, especially for local news, compared to the consolidated gigantic [laughing] newspapers, but obviously it also is a metric culture thing. It must be really overwhelming as a journalist to mention one of these groups and get, you know, 50,000 likes in an hour. That has to, you know, say something as it goes up their corporate structure. They might want to write things that are more critical and be getting an insider push of “Well, let’s just do it for the likes,” you know. There’s all kinds of context.

So I’m not saying that all journalists are giving in to all of this. But it’s definitely now part of the system that I think is…this entire concept of legitimization. That legitimization for K-pop means household names, means Grammys, means Billboard. It also includes newspapers, English-language newspapers. So they’re definitely part of sort of the shifting landscape about how do people engage in K-pop fandom.

ELM: I don’t know how much you study the music in the United States, because I do think too, like—I don’t wanna put all the blame on K-pop here. I think about this year—was it this year or last year when Lana Del Rey threw a hissy fit because someone said she wasn’t the greatest genius ever?

FK: Yeah.

ELM: Right? I think that—as you were talking, I was thinking about, I don’t know why, about like, Star Wars. And it’s just like, well, there’s still space in the press for people to have a huge range of opinions about Star Wars, right? And the people who love whatever in media fandom, in various TV or film fandoms, they can come after journalists who say negative things about them, but it’s not the same, and it’s not journalists fearful of giving a negative review to the latest Marvel film or Star Wars film, right? I mean—Flourish, don’t make that face! [laughing] You know what I mean.

ML: I think that one of—it’s absolutely true that these other fandoms behave this way, especially just popular music now. So one of my colleagues is researching similar behavior for, you know, Swifties, for Taylor Swift fans, and all of these different groups to follow. That’s not entirely new. I would say what’s really interesting about K-pop’s case is K-pop is a nationally branded genre, and we don’t even wanna really call it a genre, but it is nationally branded.

So yes, there’s lots of space in media for people to have different opinions about Star Wars, but it still tends to be this global, you know, “Oh my God, Star Wars—” if I see another thing about Baby Yoda, my head’s gonna explode. [all laugh] I’m a Trekkie, so.

FK: Yeah!! Rise!!!

ML: But I think that’s one of the big differences, is that we haven’t really had a media product with that much up-front foreignness to it that is not Anglophone foreignness—Harry Potter, One Direction, you know, going back to the Beatles. We haven’t had that in a long time and I don’t think anything has been similar since the boom for anime. And if you look at some of the newspaper articles that people wrote, like, “Do you know what an otaku is?!” Talking about people who liked anime as if they were another species.

I think that’s why the K-pop, K-pop discussions are so interesting. You can’t get around the fact that it is considered—still considered, in many ways, transgressive, especially for suburban young white women, to be interested in male Korean idols and try to, you know—you have to sit down and explain this in a way to your family. “This is what I do. This is what makes me happy.” You need, in some cases, an intervention when they don’t understand. And that’s the thing that a lot of people don’t seem to wanna talk about.

ELM: That’s really interesting, because even talking—even comparing it to anime, like, you know, BTS is nominated for Grammys, right? I can’t think of an East Asian cultural product that has had this level of—at this scale, you know. A whole range of artists, not like one movie, where people were like “Wow!” Obviously here have been some individual things coming out of various nations.

FK: Yeah, I think it’s also different to have like a fan culture in the same way.

ELM: I mean a genre.

FK: I guess there’s—there’s Hong Kong cinema, I think, would be the other. That would be thing thing, which is obviously a completely dudely fandom…

ELM: But you’re talking about fandom. Grammys brings you into kind of a mainstream cultural—or going on Jimmy Fallon, or whatever. And I’m not…no? Are you gonna say something mean about the Grammys and Jimmy Fallon?

FK: I think that Hong Kong cinema got pretty mainstream. Maybe not that mainstream, but pretty mainstream.

ELM: I don’t know, I think there’s still a sheen of like, what’s the word I’m looking for. Like, classy people like that. Like, you know what I mean? That’s not…

FK: OK. I see. This is different. Coming from a martial artists space, lots of idiots like this. This is the difference between us. [all laughing] Every idiot in the dojo or dojang loves some of this shit.

ELM: [chortling] OK! All right.

FK: And it is not classy. [laughing]

ELM: I believe that. I believe some un-classy people…

FK: I’m just saying! I’m sorry, my meathead brethren. I am with you in spirit. I too wish to make my hands move as fast as Michelle Yeoh’s do. But…

ML: And I think, I mean, when did my fandom stuff really begin? And what’s interesting is I was doing my own personal genealogy with these things: I realized that I was primed by the time that Yu-Gi-Oh! and Pokémon came along, because before that I was obsessed with Mortal Kombat and Power Rangers.

FK: Yeah!!

ELM: OK, those are pretty mainstream.

ML: And those—they were mainstream, but… Mortal Kombat was a different case, but for Power Rangers, it was completely whitewashed! You know. Nobody, if you were that young, you didn’t realize they were taking Super Sentai footage and then putting it with these white kids for the most part.

ELM: I had no idea where that came from when I was a child.

ML: You had no clue.

FK: Yeah, there’s a whole thing with it! You scratch the surface and there’s a whole genre under it and you’re like “What?”

ML: So I would say film is the closest it’s ever come, but film is extremely nation-branded. Hong Kong cinema. People who are cinephiles, they’re like “Oh, you’re interested in Japanese cinema?” And I’ll name a horror film, and they think I must mean Kurosawa, because there can be no other part to Japanese cinema. Now, having Bong Joon Ho winning the Oscar for Parasite, there’s a reason this is happening the same year as we’re seeing BTS get all the attention.

It is just, I think—this is the example I’ve been thinking about a lot in terms of both the affective hoarding and the BTS exceptionalism, but it has to do with a different group: I would frequently go to fan events for a group, a K-pop group in Tokyo, and they were so popular that some of their fans from Korea would come to the events in Tokyo, because in Japan, it was basically guaranteed they would get to have some type of, you know, handshake, autograph, photograph with the idol, whereas in Korea it was a lottery system and maybe they wouldn’t.

So some of the Korean fans would come, and some of them were extremely nice, but there was one who was known as “The Screamer.” And she was known as The Screamer because as soon as a group would come out at an event—which may have been at a shopping mall, in a Tower Records—she would just screech. And I don’t mean the screeching of “oh my God, there he is, I’m so excited.” She would screech during the entirety of the song so they would look at her. And this [laughs] made a lot of Japanese fans very angry, and it made—I mean, I was there with at the time my friend from the U.S. and also my friend from Australia, and we were very confused by this. And there were other Korean fans that did not like this behavior.

I feel like the problem is right now, a lot of the attention on BTS is just—it’s the loudest voice in the room. It’s the most apparent thing. It’s the go-to example. But that doesn’t mean it’s the entirety of it, because I certainly wouldn’t want someone to think my fandom is just how that screecher behaved. It wasn’t, even though we were there for the same thing.

ELM: You mentioned “affective hoarding” but we haven’t talked about it yet, and I need us to talk about it. So can we talk about it?

ML: Mm-hmm! Sure.

FK: Can someone define “affective hoarding” for me?

ELM: Yeah. So this is, for context—I don’t think it’s the first thing I read of yours, but it is the one that really stuck with me, and I have quoted it in many places.

ML: Yay!

ELM: And so I’m excited to discuss it. But you should summarize it, not me.

ML: OK. So my research and also my dissertation is primarily concerned with affect, and the affect that is apparent in the fandom of male K-pop groups in Tokyo, especially with their Japanese female fans.

ELM: Sorry to interrupt, but can we define “affect”? Because I think we say it a lot, kind of yanking it from fan studies, and sometimes I wonder if we should be defining it more frequently.

ML: So, for me, my working definition of “affect” has to do with the impact, emotional impact, or the capacity to generate an emotional connection of some kind—positive, negative, and everything in between—either in an interaction between a fan and an idol, if we’re talking specific to fan studies.

But this comes from a long study of workplace situations, so going back to how does one show affect if you are in the service industry, how does one show affect attached to someone’s gender role or their profession. Does that make sense?

ELM: Yeah, so it’s the emotional response, right? And the emotional relationship.

ML: And I think that you know, fandom has always been about affect, if you think—if you mention fandom to someone who is not versed in fan studies, or that you just ask them to think of popular examples, what do they tell you? It’s probably girls screaming at the Beatles, people in line to see Star Wars, you know, going to a screening for a Marvel film and people crying because of what happened. So fandom has always been about affect.

I was particularly interested in studying the affective engagement between fans and idols, because I think that in the Anglophone sphere, idols are untouchable. We basically write about them, but only a few, select few—so journalists or maybe if you’re at some event—will get to have any type of interaction with them. But in Japan, which is K-pop’s biggest market outside of Korea, there’s an entire system built for affective engagement between fans and idols, in terms of just talking—having conversations, but also being physically close, forming friendships, knowledge bases about each other to the point where they might ask, you know, “How’s your niece doing? I heard she was in the hospital, I saw it on your social media.” These things are more normal there, and that’s what I researched.

FK: You mean an idol might know that about their fans as well as the fan knowing it about the idol, wow.

ML: Oh, yeah.

ELM: Because the fan has paid for access…?

ML: The fan has not only paid for access, but in many cases it’s…things are set up so that way you don’t have to pay. So you can be just present enough [laughs] that they will eventually remember these things about you and it gets really weird.

FK: It’s like being the person who goes to every Supernatural convention.

ELM: Yeah, number one.

FK: I’m calling out Supernatural just because they’re the most convention-friendly sort of, you know.

ELM: Yeah, but that’s not a great example because at Supernatural conventions you can pay for more access.

FK: Yeah, but you’re paying for more access presumably there too, but like, will they remember you? Not just because you paid, but because you…

ELM: You’re always the one in that one room…

ML: It’s somewhat connected.

ELM: Right? Like…Jared Padalecki’s gonna notice you, right?

ML: It’s somewhat connected, and it also has to do in terms of scale and frequency. So I realized the other day, when I was giving a lecture and I was trying to remember what my schedule was like when I was doing my fieldwork I was oftentimes spending eight hours a day three days a week with idols. That that was just what I did. I saw idols more than I went to class. And I didn’t skip class! It was just that was how much time was invested. And you really get to know each other when that happens!

And also, with the tiers of idols I was working with, which were more rookies, people on the middle tier, they were extremely accessible. You could go to them after a concert and say “Good job! Here’s a beer” and hand them a beer and that was fine and that could happen. Things that you wouldn’t even think of doing, especially in the U.S., where the difference between idols and fans is just, you know, barricaded as much as possible.

People often ask me, “Why don’t we get to do things like take selfies as often with idols in the U.S.?” And it’s very simple: that the companies do not trust Americans, that Americans have a terrible reputation in terms of not following boundaries, and that the transcultural gap is too big because of trying to speak English or someone trying to use Korean if they don’t properly know how to use Korean.

So in these spaces, I saw this behavior, and I decided I finally wanted to call it “affective hoarding,” which is not just “I’m accumulating subcultural capital in the space,” right. “I show up to every event, I am always here, I know all the stuff.” That’s the subcultural capital we’re used to talking about for fandom. Affective hoarding, to me, was fans doing things for the specific reason of taking it away from another fan.

So I think I used multiple examples in the article, but one of them was they had a random photo system where the staff would go backstage, take a bunch of Polaroids, put them in a box that you felt like you were in a game show. You would pay 500 yen, so like five bucks, and take one out. If you picked one that was signed, you got to have a five-minute date with that idol. Don’t get me started on the five-minute date, or do get me started, whatever you want. [laughs]

But you were also at the risk of, I might get a picture that’s not the idol that I’m a fan of. Well, what do you do with it? It’s a candid photo. It’s considered to be, for another fan, probably priceless. Do you give it to them? Do you give it to them with an eye on them doing you a favor in the future—which happened to me multiple times, where people would do that? Do you sell it to them? How much do you sell it to them for? Or do you keep it, even though you don’t like that idol, because you don’t want them to have the photo?

And this happened so much that I really wanted a term for it. I think it happens across fandoms, absolutely, but it’s—it’s really the difference being that, even though it might have to do with accumulating, you know, something rare or collecting that we might be used to in a lot of other fandoms, it’s the specific thought of: “I want it because I don’t want this other person to have it,” or “I’m gonna keep it because I don’t want this other person to have it.”

FK: It’s sort of a zero-sum game piece, right? It makes me think of some of the interactions that you see at Comic-Con.

ELM: Yeah, I was thinking about that too.

FK: It makes me think of even things like, you know—I mean, it happens with parties, but it happens also with like objects, all sorts of stuff. And I feel like…

ELM: It happens, they’ll say like “Oh, you all got into this room, and think about all those people out there still sleepin’ on the sidewalk!” And everyone’s like “Yeah!!!” And it’s like, “OK…you’re cheering that a bunch of people didn’t get in and they still have to sleep on the sidewalk?” Like, that’s about being—it’s not just about you getting in, it’s also about you getting in over them, right?

FK: You being on top, right. Yeah. It’s sort of interesting cause it’s like, I wonder—I wonder if it’s the same, though. Because I feel like at Comic-Con, usually, it’s more like: “I feel good because I’m on top.” At least that’s been my experience or I’ve seen, “I feel good because I’m on top, and someone has to be lower down for me to be on top.” Like, “We can’t have a mutually beneficial relationship, if I’m gonna be the top fan, that means there are other people who didn’t get into the room, who aren’t here, who are less exclusive.” But that’s not exactly the same as “I want to have this, which would give you joy, and I don’t even care about it, but I’m gonna keep it,” you know what I mean? I feel like that’s a little bit different. I don’t know.

ML: Yeah. I mean, it was, it was a really interesting phenomenon to witness. It was also some of the moments that were the most difficult for me in the course of my research, and I think I also talk about it more in Rukmini Pande’s upcoming book—no, it’s released now! Fandom, Now In Color: A Collection of Voices, where I have a chapter on basically the bad experiences I had during my fieldwork and what they especially had to do in terms of my subject position as being multiracial and being American—and being a researcher in these spaces.

So you also have to remember that for a lot of the spaces I was in, people knew I was researching, and that was its own weird label to try and deal with. But it absolutely was in some cases people saying, “I will take this home and burn it before I give it to that person.” And it’s…

ELM: Fascinating.

ML: Very, very…I have an album on the shelf next to me that has all of those types of photos in them, so it’s really interesting to look at it and think, “Yeah, that is very odd.”

FK: I’m sad, because we’re running out of time and now I just feel like—people are bad.

ELM: Flourish, you already thought that.

FK: I already thought that but it’s not helping my view about the human race.

ELM: We are running low on time, but I think as a final question—Fandom, Now In Color, edited by Rukmini Pande, you are one of the contributors: can you tell us anything more about your essay? Because we are very excited to read it.

ML: Sure! So my essay in the book is called “But I’m A Foreigner Too: Otherness, Racial Oversimplification, and Historical Amnesia in Japan’s K-Pop Scene.” And I really appreciated that it was a space for me to collate some of the more negative experiences that I had that had to do with my own identity, being multi-racial and being American, in spaces where primarily it was Korean idols and Japanese fans.

And I think for a lot of people, the discussion of even Japan’s colonial history and the impact that has on K-pop idols when they go to Japan to promote—the transcultural differences even just between Korea and Japan, but then to add in me as an American and the politics of utilizing the English language, the difference in English-language education between Korea and Japan? So there were often times where I could speak with an idol very fluently in English, because he had studied abroad or he had used it for some other reason in Korea, and then I would have Japanese fans be mad at me, because that was considered too intimate. It was way too friendly.

I mean, it was really a nice piece to be able to work out the frustrations I’ve had in academia writ large, of people coming up to me and thinking it’s OK to ask, you know, “What are you? Why do you look that way and why is your name what it is?” [laughs] Which still happens! And I think is the type of topic that with some of the—hopefully—some more of the awareness around BLM and also just access for BIPOC scholars, young scholars, and also in higher education overall…it’s hopefully a bit of representation that someone could read and say, “Wow. I have also had a difficult experience going into this space that I thought was safe, that I was excited about, that spoke to my fannish interests, and I didn’t realize that this would be the thing that people would pick on or people would end up talking about.”

And I think it’s not only about race, but also class. For me growing up, from a single-parent household and with a mother that worked multiple jobs, being in academia at all is sort of a fever dream sometimes. And then going to Japan to do this research was, I mean, it was a really amazing experience for me, but that doesn’t mean that I don’t want to talk about the difficult things. Which is the same thing, I think, as the ethos for basically every piece I write. There are good points, there are bad points, and the entire spectrum is the thing that’s important and that context is what’s important.

FK: I think that’s—I mean, I can’t wait to read your essay, and I think that’s a really wonderful sort of wrap-up point to sort of sum up your whole vibe, I guess.

ELM: Yes! Great vibe. [laughs]