Towards a Definition of “Fanfiction”

3,564 people took our survey. Here’s what we learned.

by Flourish Klink

As a podcast, Fansplaining is pretty passionate about fanfiction. We’ve run a survey on fans’ favorite fictional tropes, declared war on the dictionary over a misplaced space, and held forth on Mary Sues. But if we don’t even trust Merriam-Webster to spell “fanfiction” correctly, how can we trust any dictionary to define it? So earlier this year, we ran the Fansplaining Definitions Survey, which claimed to “help us come to a collective definition of what ‘fanfiction’ means.”

But the purpose of the survey wasn’t to simply poll people and declare the most common answer the official definition. We wanted to to encourage a large number of people to think about how they reach that definition—and to get them to write about it. We proposed some ideas about “fanfiction” in our first question: that it might be derivative or transformative, that who wrote it might be important, that its commercial or noncommercial status might be make a difference. Then we gave room for people to write their own definitions, and to respond to us throughout. You might consider it a mass-scale brainstorming effort, led by Fansplaining.

It’s been a month since the survey closed, and in the end, 3,564 people took it. Respondents answered 40 questions, many of them long-format; there’s a lot of data to chew through! In the latter half, respondents took their ideas about the boundaries of fanfic and applied them to individual written works. But this article will focus only on the first two sections of the survey, where people attempted to set those boundaries as they defined “fanfiction.”

The Multiple Choice Answers

In the first section, respondents were given a series of nine questions, all starting with the phrase, “Must fanfiction be…” Each respondent saw them in a different order. The questions made one big assumption: fanfiction is (or is often) work based on another source work. There’s other ways you could choose to come at a definition of fanfiction—we’ll get to those in the next section—but we intentionally framed it this way as a starting point.

Respondents could choose to respond to each of these questions in one of four ways:

Yes, to be considered fanfiction it must be.

Some works of fanfiction are, and some aren’t.

No, a story like that is never fanfiction.

I don’t know (or it’s not relevant).

(In retrospect, we probably shouldn’t have used the word “story” in the answers. It would have been better to phrase it as “No, something like that is never fanfiction.” Hindsight is 20/20.)

The results might have been disappointing if we were trying to use these questions to “really” get at a “real” definition of fanfiction: for most questions, most respondents chose the answer “Some works of fanfiction are, and some aren’t.”

| Must fanfiction be... | Yes, to be considered fanfiction it must be. | Some works of fanfiction are, and some aren't. | No, a story like that is never fanfiction. | I don't know (or it's not relevant). |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ...based on another work of fiction? | 1449 (40%) | 2029 (56%) | 14 (0.4%) | 72 (2%) |

| ...based on real events or people? | 35(1%) | 2938 (82%) | 301 (8%) | 290 (8%) |

| ...written by someone other than the original author of the work it's based on? | 2588 (73%) | 831 (23%) | 43 (1%) | 102 (3%) |

| ...written for a community of fans? | 1164 (33%) | 2191 (61%) | 19 (0.5%) | 190 (5%) |

| ...written by a member of a community of fans? | 1304 (37%) | 2036 (57%) | 19 (0.5%) | 205 (6%) |

| ...not endorsed by the original creator? | 339 (10%) | 2432 (68%) | 91 (3%) | 702 (20%) |

| ...transformative (i.e., not just a rehash of the original work, but changing some aspects of the world)? | 928 (26%) | 2506 (70%) | 26 (0.7%) | 104 (3%) |

| ...distributed free of charge (that is, the reader doesn't have to pay money for it)? | 1146 (41%) | 1921 (54%) | 16 (0.4%) | 182 (5%) |

| ...not for profit (that is, the author doesn't earn money for it)? | 1271 (36%) | 2029 (57%) | 30 (0.8%) | 234 (7%) |

The notable exception? 73% of respondents said that in order for something to be considered fanfiction, it must be written by someone other than the original author of the work that it was based on. By that standard, prequels and sequels can’t be fanfiction, nor can books with intertextual relationships to an author’s other works, like Carry On by Rainbow Rowell. If you listen to our podcast, you may know that this is one of Elizabeth’s bugbears and that she feels very vindicated.

Also interesting: 82% of respondents said that some works of fanfiction are based on real events or people. (For what it’s worth, 1% said that fanfiction had to be based on real events or people. We have questions.) But 40% of respondents also said that fanfiction must be based on works of fiction. That means that at a minimum, 25% of respondents think both that fanfiction is always based on works of fiction and that fanfiction is sometimes based on real events or people! How can both things be true? Three possible answers come to mind:

They’re thinking of fanfic based on historical fiction, like Hamilton fanfic. In other words, they’re saying that works based on fictional works that are based on real people can be fanfic.

They consider celebrity personae and tabloid narratives to be works of fiction. In other words, they’re saying that our perceptions of celebrities are already works of fiction, so real person fic, or RPF, is both based on real people and on fiction.

They’re confused or didn’t remember the questions they’d already answered very well.

Since we’re not psychic, we don’t know which of these three explanations (or something else entirely) were on the minds of our respondents. But people certainly did have a lot to say about RPF when they wrote their long-form definitions of fanfiction…

The Long-Form Answers

The next question invited people to respond in long form to the prompt, “Please define fanfiction.” The section header read, “In this section, you’ll define terms in your own words. We know that this can be difficult. Just try your best! If you aren’t sure how to write a definition, look at a dictionary (may we suggest Merriam-Webster?) for inspiration.”

The results were extremely various. Some were simple:

Fiction about someone else’s characters.

Others were complex:

I feel like there are two usages that are helpful and reasonably accurate, depending on context. There is the broad “everything is fanfiction” version, which is just “transformative = fanfiction”—and this is useful when contesting the notion that fanfic isn’t valid, creative, &c. because it is rooted in prior canons. There is also the somewhat narrower definition, which I like better (because I am privileged enough not to have to have the above argument very often.) The narrower definition I use is that fanfiction is a modern phenomenon that came into being precisely because of the cultural shifts surrounding the value of originality: once it became important to have new ideas, and possible to claim them as one’s property, then transformative narratives became a marked category in a way they hadn’t been before—so fanfiction calls back deeply to earlier modes of narrative engagement, and hits some deep spot in us that is ignored/denigrated by Enlightenment (and most post-Enlightenment) thought, but is distinct from them because it has had to carve a path for itself through modernity. I am also personally inclined to think that it’s useful to distinguish fanfiction from e.g. pastiche, insofar as its creators are more horizontally related to their readers, with regard to all kinds of capital (economic and establishment-cultural most of all) but I am less wedded to that part.

Some of our favorites were just straight-up funny:

Fanfiction is a story written by a person in the fandom because breaking into the creators office and telling them that everything that they did is wrong and rewriting it is considered “rude” and “illegal”

To try and make some sense of this mass of information, we coded each entry by themes that emerged from the data. For example, every time a response mentioned that fanfiction was written to celebrate a source text, out of love for a source text, or as a tribute or homage to a source text, we coded it as “Purpose: Love.” (88 out of the 3564 responses were coded this way, or about 2.4%.)

It’s important to remember that just because a response was coded to include “Purpose: Love” doesn’t mean that it didn’t mention any other possible purposes for fanfiction. (“Purpose: Critique” and “Purpose: Fun” were two other codes, and several responses included all three.) It also doesn’t necessarily mean that if you asked other respondents, “Is fanfiction usually written to celebrate its source text?” they would disagree. They might disagree, but they also might agree and simply have left it out of their definition because they took it as a given, or because they didn’t think it was significant.

Fanfiction is derivative of another work

Looking at the answers as a group, there are two basic clusters of answers. The first is the “formal cluster.” Here are some examples:

A written work that is based on a situation or characters that exist and are borrowed from any form of published media.

Fiction based on an existing story, character, fictional world, person, or scenario that the author got from somewhere other than their own imagination, and which retains some meaningful connection to that originating material rather than simply using it as inspiration

Any work of fiction that takes inspiration (characters, events, etc.) from a preexisting work.

88% of responses contained some sort of reference to the concept that fanfiction is derivative work. The formal cluster of responses privileged that aspect of fanfic, putting it front and center. They seemed to be particularly interested in defining fanfiction as compared to other, less derivative works.

In some cases, these definitions were intentionally far-reaching. After all, what work of fiction couldn’t be said to take inspiration from a preexisting work? In Western literature, the “canon” (especially the Bible) is embedded in the DNA of a staggering number of books. Fanfiction may be more explicit about its borrowing than other literary work, but not by much.

In other cases, respondents seemed to believe there’s a difference between fanfiction writers’ borrowing and other writers’ borrowing. Definitions of this latter type leaned on the Romantic idea of the author, whose inspiration springs from nowhere, or from deep inside their soul. (We…don’t agree with these people. But they have an opinion and they are allowed to have that opinion. We say, gritting our teeth.)

Fanfiction is written by and for fans

The second large group of answers we received is the “context cluster.” Some examples:

Written content created by fans for fans

A Fanfiction is a story (short or long) written by someone who earns no money for herself/himself or to share it to the community.

Fiction written by fans, using characters and/or a world that is usually the creation of another author (though not always—RPF). It’s fans using characters to explore ‘what if,’ to fix parts of the narrative they didn’t like, to add t/extend the narrative, to deepen it—or to plonk the characters in a totally new world. Primarily done by fans, sometimes for themselves, sometimes for others, usually not for profit. It’s born out of love.

These responses focus on the context in which fanfic is written: who writes it, and who reads it. They seemed to be interested in defining fanfiction against other types of work created by people who aren’t fans.

Let’s note: We say the context cluster is a “large” cluster, but it was significantly much less common than the formal definitions: 31% of respondents said that fanfiction was mostly or usually written by fans, 11% of responses said that fanfiction was written for fans, and smaller percentages suggested that it was amateur or written outside of professional contexts.

We have a guess as to why there was such a gap between people who said fanfiction was written “by fans” and those who said it was “for fans”: many respondents made it clear that a written work could be fanfic even if it was never shared with anyone—if it was written just for the author themselves.

Why are these two types of definition so common?

Well, for one thing, respondents were primed to answer in these ways! If you scroll back up to the multiple choice answers, you’ll see that they center these concerns. In fact, people mentioned all of the themes that appeared in the multiple choice questions more frequently than other ideas about fanfiction. That’s only to be expected.

But that can’t be the only reason why these definitions were so common. We think that they really do get at the heart of how people think about fanfic: first, as work that’s derivative of other work, and secondarily as work that takes place in a community of fans. (Hardly groundbreaking research.)

Or, it could just be that our survey-takers know how to Google, and Fanlore’s “fanfiction” page begins with the following sentence:

Fanfiction (fanfic, fic) is a work of fiction written by fans for other fans, taking a source text or a famous person as a point of departure.

So let’s move on to the more interesting part of the survey: the other, less-commonly mentioned things people said about fanfiction. What new ways of thinking about fic did our respondents offer?

Fanfiction is not for profit

OK, this isn’t exactly an unusual or new way of thinking about fanfic, and a lot of respondents mentioned it—34%. It’s hardly surprising, but it does suggest that for a lot of people, commercially published works like 50 Shades of Grey and commissioned stories about established worlds on Wattpad don’t count as fanfiction. (Later questions on the survey explored this topic, so we’ll leave it at that for now.)

Fanfiction is based on popular texts

Some respondents said that fanfiction had to be based a popular text—a large entertainment franchise, or a work by a famous author, or a work that had a fandom. A story based on an unknown text wouldn’t cut it.

There are certainly edge cases that contradict this assertion: we don’t think anyone would say that works written for the Yuletide Challenge aren’t fanfic, but many of them are based on works that aren’t popular, and by definition, Yuletide is for works about source texts with little to no fanfic online. On the other hand, this idea highlights fanfic’s relationship to pop culture: it reflects Henry Jenkins’ classic argument that fanfic writers are “textual poachers,” asserting public ownership over the blockbusters and must-see TV that are our modern myths.

Fanfiction is a rebellion against the status quo

A number of respondents said that fanfiction allowed fans to create better representation of minority groups, or that it is a rebellion against the entertainment industry. We have mixed feelings about this argument: fanfiction isn’t always unwelcome to the entertainment industry, and it definitely hasn’t been equally kind to all underrepresented minorities. (We’ve covered some of these objections on our podcast in the past—Episode 29, “Shipping and Activism,” in particular.) But the argument is definitely present in a strain of scholarship about fandom, beginning in the early 90s and continuing today. If you’re interested in learning more about this idea, the Journal of Transformative Works and Cultures is a good place to start.

Fanfiction is an umbrella term for works in any medium (or isn’t)

Many respondents specifically called out fanfiction as textual, and some people included fan comics. Some went so far as to specify that fanfiction must be narrative, or must be prose. A small minority, though, considered “fanfiction” an umbrella term including fan-created art in every medium. Similarly, some people specifically included—or excluded—meta, nonfiction fanworks that celebrate, critique and interpret source material, from their definition.

We’re pretty agnostic on this subject, but we would like to point out that many people use the term “fanworks” as an umbrella term. We use it on the podcast because it more clearly includes things like fan films and meta, and keeps fanfiction as a term for primarily textual fiction, which otherwise doesn’t have its own name.

Fanfiction can be any length

Several people specified that fanfiction can be any length. One of the most notable aspects of fanfic is that it’s not limited in size. Conventionally, novels can only be so long and short stories can only be so short. In the world of fanfic, though, hundred-word drabbles are posted cheek-by-jowl with the longest novel ever written by a human. (It’s a Super Smash Bros. fanfic, The Subspace Emissary’s Worlds Conquest, and it clocks in north of four million words. The next longest contender is half its length.)

Fanfiction includes shipping, or includes fandom tropes

Less than 1% of respondents said that fanfiction usually or always featured shipping, or featured fandom tropes. No one listed this as the sole qualification for a work to be fanfiction, but it’s an interesting perspective, because it’s one way to differentiate a fanfic from a highly allusive work of literature. Works of literature can be as referential as they like; they can even be referential to objects of fandom; but if they don’t participate the trope or ship concerns of fandom, then they don’t count as fanfic.

If this idea were taken to an extreme, stories without ships or tropes wouldn’t count as fanfic, even if they were written by fans, for fans, not for profit, not with the involvement of the original work’s creator, and posted on the Archive of our Own. But it’s not really wrong to say that most fanfic partakes in tropes or ships—many stories have both!—so maybe we shouldn’t dismiss the idea out of hand.

Fanfiction includes Real Person Fiction

It should hardly be surprising that many people covered the issue of Real Person Fiction, also known as “Real Person Fanfiction” or “RPF,” in their definitions. After all, the multiple-choice questions asked about the issue.

What’s interesting is that while several long-form responses expressed ambivalence about RPF, mentioning that the author doesn’t like or read it, almost nobody explicitly excluded RPF from fanfiction in their long-form definition, and 21% of respondents explicitly included it. It seems that the 8% of multiple-choice respondents who didn’t think RPF counted as fanfiction didn’t think it was central enough to the issue to explicitly exclude it in their long-form definitions.

Fanfiction isn’t plagiarism (but it might violate copyright law?)

Many people included commentary on fanfiction’s relationship to copyright law or to plagiarism. Generally speaking, people seemed to agree that it was both legal and ethical to write fanfiction, but they were fuzzy on why. Some people said that fanfiction was legal only as long as it was not for profit; others said it was legal because readers understood that it was derivative and didn’t think it was “official” (neither of these statements are entirely accurate).

We were surprised at how many respondents didn’t understand the differences between plagiarism, copyright infringement, and trademark infringement. (We see these same confusions when authors famous for denigrating fanfiction talk about how fic writers are “plagiarizing” their work. Not to name names.) We definitely don’t have space to write an explainer here, but if you aren’t positive you understand these issues as they pertain to fanfic (or even if you are), we suggest the blog F Yeah Copyright, or Fansplaining Episode 4, “Buncha Lawyers.”

Demographics

As part of the survey, we asked respondents to answer some questions about demographics. What we found shouldn’t be interpreted as “these are the people who read fanfiction”: it should only be interpreted as “these are the people who took the survey, and had enough stamina to stick around to the end.”

On the subject of gender, the split was pretty stark:

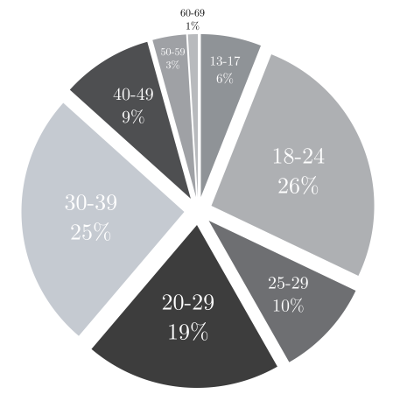

Our age data is a little fuzzier because about 300 people took the survey while incorrect age categories were in place (oops), but we still feel pretty confident when we say that we got a wide range of ages:

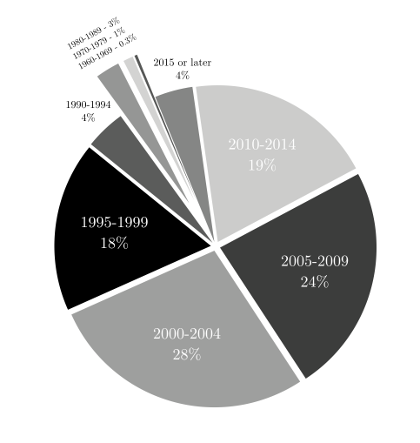

We also asked the respondents who self-identified as fans when they got involved in fan culture:

We weren’t all that surprised to see that most respondents reported they’d joined fandom after the advent of the internet, but it was fascinating to see how that breakdown actually played out.

So we got all this great demographic data: now, what are the interesting correlations between respondents’ demographics and their responses? By the time we got to this part of the analysis, Flourish was a crispy fried researcher—you try hand coding 3,500 free response answers with a short deadline—and friend of the podcast PorcupineGirl stepped in to save the day, run the numbers, and generally provide analysis; the remainder of this section consists of her insights combined with our speculations about causation.

PorcupineGirl focused her attention on the long-format answers, and it turned out that very few subjects correlated strongly with anything. All groups of respondents mentioned that fanfiction could include RPF about as frequently; they mentioned that it was derivative about as frequently; they said it was written by fans about as frequently. There were, however, two exceptions.

Fans from the early 90s care about fanfic being not-for-profit

As you can see, respondents who joined fandom in the 1990s were more likely to mention that fanfic is usually or always not-for-profit than respondents who joined fandom in other eras—more than twice as likely than respondents who joined fandom after 2009, in fact.

We’ll need to do some more research to determine if this is true, but our current theory is that fans from the 1990s remember the beginning of the online fanfiction era, when IP owners were cracking down on fanfiction—and the one way to make sure you weren’t targeted was to be clearly not-for-profit. Those who joined earlier might have stronger connections to zine culture and the culture of SFF cons; those who joined later were shaped more by stories of fans fighting back against copyright overreach, and then, later, the way that Wattpad and other similar sites monetize fanfic.

Longer-term fans distinguish between fans and pros

Examining the data further, PorcupineGirl created a cluster of codes that signaled distance from professional writing. Responses in this cluster said that fanfiction was “unauthorized,” that it was “not written by the original creator,” that it was “not for profit,” that it was “distributed for free,” or that it was “amateur,” “unprofessional,” “noncommercial” or “nonliterary.” The results were striking:

People who had been in fandom longer were much more likely to express this type of sentiment. A person who joined fandom in 1990 was just a little less than twice as likely to do so as a person who joined fandom in 2010.

To us, this suggests that the borders between amateur and professional writing have become more porous in the past ten years. Anecdotally, this seems to be the case: Wattpad’s FANtasies, Kindle Worlds, and the successes of original novels by writers who also admit to fanfic (His Majesty’s Dragon), of stories “with their serial numbers rubbed off” (50 Shades of Grey), and of YA novels about fanfic writers (Fangirl) all point to a wider mainstream acceptance of fandom and fanfiction. We think that newer members of fandom are more likely to take this situation as the status quo, whereas those who have been in fandom longer are more likely to see themselves as very separate from the professional world.

So what can we conclude from all of this?

This article necessarily only represents some early, first conclusions. As we’ve mentioned, the survey was 40 questions long; this article only covers the first few. We’ll be posting a lot more, and our conclusions may change as we dive deeper into the rest of the data. But even then, we probably won’t be able to tell you a single, final, and definitive definition for the term “fanfiction.” We’d love to, but it just isn’t possible—not as an outcome of this survey, nor as an outcome of any other survey.

Definitions of fanfiction can orient themselves in different ways. They can be formalist (“What is this text? What are its features?”) or social (“Who was it written for? Who wrote it?”) or affective (“What mood was the writer in? What mood does it seek to inspire in readers?”) or socio-economic (“What political and economic structures does it exist in? What does it challenge?”) A good definition might take more than one of these tactics, depending on its context. When one argues that their fanfiction should be permitted in a creative writing class, they might choose to highlight fanfic’s formal similarity to literary works like The Hours. When they claim that fan culture is complex, deep, and not merely consumerist, they might point to the social and gift-giving elements of fanfiction culture.

Our respondents thought a wide diversity of fanfic’s aspects were important, and they didn’t always agree on every detail. By far, though, they agreed that the most important aspect of fanfic is formal: fanfiction is work based on another work. And the newer to fandom they were, the less likely they were to draw a clear line between “fanfic” and “original fiction.”

And maybe that’s the point: there is no clear line. Fanfiction is what authors claim to be fanfiction, and what audiences accept as fanfiction. Different people’s viewpoints may be slightly different, but like Justice Potter Stewart defining pornography, “I know it when I see it.”

This article is brought to you by Fansplaining’s patrons. If you’d like to help us publish more writing like this in the future, please consider pledging as little as $1 a month.

If you’d like to check our work or do your own analysis, we’ve made the full data set available to the public, as well as the coded long-form responses to “please define fanfic.” They’re released under a CC-BY license, so feel free to make use of them as you like, just remember to credit and link back to us!

Flourish Klink co-created and co-hosted Fansplaining from 2015-2024. Formerly, they worked in fan culture and audience research for major media franchises; now, they are pursuing the priesthood in the Episcopal Church.