The Ever-Mutating Life of Tumblr Dot Com

Reports of the platform’s death have been greatly exaggerated

by Allegra Rosenberg

“The Premature Burial” by Antoine Wiertz

This article is brought to you by Fansplaining’s patrons. If you’d like to help us publish more writing like this in the future, please consider becoming a monthly patron or making a one-off donation!

To be an active Tumblr user in the year 2020 is a curious thing. If you’re able to curate a circle of other active users to follow and engage with, the platform is as vibrant as ever, with hundreds of thousands of blogs churning out writing and memes and art at a rapid clip.

But mentioning the site—or even a mere glimpse of the app on your phone—is enough to bring out cries of shock, disbelief, and condescending nostalgia.

“Wow, I had no idea Tumblr still existed.”

“Oh my God, you still go on Tumblr?”

“Haha, oh man, I remember Tumblr.”

I then have to choose how much to reveal—whether to expose myself as a passionate member of the still-faithful, or to simply laugh it off and change the subject, lest I be judged harshly for my continued membership in the Fellowship of the Cringe.

I joined Tumblr as a 14-year-old in early 2010, stumbling across various Doctor Who fanblogs dedicated to different David Tennant body parts. I fell fast and hard for the easy-to-use interface, which allowed me to reblog everything from silly memes to gorgeous graphics and long rambling text posts. Thanks to Tumblr’s tagging system, it was easy to find people with similar interests, and I quickly made tons of friends and racked up followers during a very formative period in my life.

After four years of dedicated use, my eventual break from Tumblr was a fairly natural thing. I went off to college, and ended up pointing my fannish passions towards endeavors that were less suited to a purely online interface—specifically, local indie music and live concert promotion, the obsessions that put me on my current career path in the music industry. I tackled those interests with the same intensity that I’d brought to my fandom activities in the past, but Tumblr fell by the wayside in the meantime.

It was a combination of factors, including obligatory post-college emotional aimlessness and, very importantly, the release of Amazon Prime’s Good Omens miniseries, that found me rejoining Tumblr as an active user in early 2019, and starting a new account basically from the ground up.

Immediately, I was fascinated to see how much had changed—and how much hadn’t.

The last time I’d been an active Tumblr user by any measure was 2014. The year prior, Tumblr had been purchased by Yahoo—and Marissa Mayer famously promised “not to screw it up.”

Three years later, Yahoo itself was bought by Verizon, and these two acquisitions in quick succession induced a general mood of uncertainty amongst users. What sort of meddling could Tumblr be subject to, under the purview of corporate overlords who didn’t really seem to know what to do with their ugly-duckling asset?

Fast forward to 2018. A complex combination of factors—including the passing of the federal SESTA-FOSTA law to ostensibly combat sex trafficking, and issues with Apple’s App Store and its provisions against apps containing adult content—led to Tumblr enacting a ban on NSFW content across the platform. A major uproar ensued, and Tumblr’s long-standing communities devoted to both real-life and illustrative pornography spoke out against the restrictions.

Most mainstream media coverage of Tumblr since the porn ban has focused on the subsequent decline of the website. Business Insider reported in late 2019 that Tumblr’s unique monthly visitors had decreased by more than 20% in the year since the porn ban.

Some of the immediate exodus can be blamed more or less directly on Tumblr’s ineffectual and glitch-ridden implementation of the filtering systems designed to enforce the ban. Going hand-in-hand with Tumblr’s instantly-viral policy on “female-presenting nipples” was the equally mockable AI-driven flagging algorithm, which in its overzealous quest to purge Tumblr of all inappropriate content swept up many an innocent post and picture. By the time both the software and the appeals processes had been ironed out a few weeks later, many Tumblr users who hadn’t even run NSFW blogs at all had abandoned ship, due to pure annoyance.

And when Verizon finally sold the platform to Wordpress owner Automattic in August of 2019, it was for a paltry $3 million, a ludicrously massive drop from the $1.1 billion valuation it had upon its initial acquisition.

Thanks to these data points, narratives about “the end of Tumblr” from people who no longer or never used the platform have become commonplace. Tumblr’s current user base—if acknowledged at all—is consistently characterized as a shambling zombie of a community, a dead platform walking.

But I’m here to say that reports of Tumblr’s death have been greatly exaggerated.

While Tumblr was certainly known in some circles for being a haven for NSFW content, that was certainly never all there was to it. For every user that decamped for greener, smuttier pastures when the ban was put into place, there was another user that simply shrugged their shoulders and kept on blogging.

For me personally, pornography had never been central to my use of Tumblr, and returning not long after it was rolled out, the porn ban didn’t affect me in any meaningful way—save receiving far fewer notifications that posts tagged #nsfw were being blocked, perhaps. (Thank you, Xkit!!) I was actually legitimately relieved that I no longer had to deal with the threat of surprise dash-dicks, which had been a steady constant since joining the site.

And I’m definitely not alone in this. The concept that Tumblr was only ever good for dirty gifs is a fallacy, one that existed long before the NSFW decree. It was perpetuated by single-minded coverage of the ban and its aftermath, which was probably the first time many members of Media Twitter had cause to think about Tumblr since that time in 2011 they used it for a few months as a writing showcase and then completely forgot about it.

But there’s a fundamental question of what the “death” of a platform even means, and whether the ever-looming “decline” of Tumblr is simply a misinterpretation of what might eventually become a new and different phase of its existence.

Ryan Broderick, a writer for BuzzFeed, said something that caught my eye in a recent edition of his weekly internet round-up newsletter, “Garbage Day.”: “The nature of Tumblr has been changing a lot recently. People are talking to each other more, using it for general-purpose blogging and discussion. I can’t tell if that’s because it’s becoming smaller or if it’s finally growing again.”

This paradoxical observation points out something unique about Tumblr’s place in the greater social media landscape. What does it mean for a network to reach a certain height and then proceed to descend gracefully from it, rather than crashing, burning, and dissipating entirely? Tumblr isn’t quite following the template of slow-burn decline that characterized the steady evaporation of platforms like MySpace and LiveJournal, in which an exodus of users over time left behind so many dormant blogs and broken links—abandoned ruins of formerly populous and active communities.

Contrary to expectations, Tumblr users have stuck around en masse, making the kind of sardonic posts the platform’s long been known for, all the while feeling like survivors in a post-apocalyptic landscape. And if you know where to look, you can still spot new blogs being started by young teens, a constant injection of youthful activity into the platform.

Just as the kind of transformative fandom that has long found a home on Tumblr plays with default expectations around narratives and relationships, Tumblr’s continued existence simply refuses to slot neatly into any of the greater industry’s standard storylines.

A late 2019 article in The Atlantic that reflected on the year since the porn ban postulated that Tumblr had become characterized by content “regurgitated from other sites—or bland continuations of aesthetically unchallenging trends that have been popular for years.”

To me, this seems like a massive misinterpretation of the platform today—though it’s one that reflects the disregard for Tumblr’s continued cultural standing that is all too common in mainstream publications.

From what I’ve observed, more than half a decade past what might be considered its “peak” as a social network in a broader, mainstream context, Tumblr remains at the heart of an ecosystem that stretches far past the site itself, exerting continued influence across the social web. To those with even a cursory amount of familiarity with the platform, it’s clear how much of the past decade’s aesthetic and memetic activity Tumblr has been responsible for.

Throughout the years, Tumblr has consistently been the ground-floor generator of an incredible amount of cultural movement. It was at the forefront of this past decade’s changes in the ways creators and brands interacted with fans, and spawned the careers of writers who are now dominating the fields of animation and SFF literature. That’s not even touching on the idea that the memetic battleground of Tumblr vs. 4chan the early 2010s was the direct precursor to the contemporary culture war that spawned our current political situation, convincing evidence of which can be found in the 2014 observation by one Tumblr user that anticipated the online alt-right movement.

And to this day, platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, Reddit, and Imgur still consistently depend on Tumblr’s highly active and unbelievably creative user base as a source for their own content. Individual outlets, most notably BuzzFeed, have long mined Tumblr for their own verticals, often prompting consternation from users who’ve found their posts reappropriated as part of clickbait compilations.

On Twitter, Tumblr threads are a common sight, like this hundred-plus-tweet-long thread by Twitter user @adinaastra, which collects popular and funny Tumblr posts into easily retweetable chunks. Similar practices are common on Instagram, where entire accounts are dedicated to repackaging screenshots of viral posts into swipeable carousels, destined for the algorithmic Explore page of millions of users. Six million people follow Tumblr’s official page on Facebook, which repackages some of the platform’s funniest posts in digest format, lifting them out of their native habitat for the purposes of external consumption.

Lucy, 19, is @tragedycamp on Tumblr and has authored such iconic posts as “twitter makes me so uncomfortable because weirdness on there is so performative… when someone is weird on tumblr you know they’re eating drywall in real life for real…” (2019). She’s gotten used to her posts ending up on Instagram, often times reaching the kind of IRL audience that can appreciate good posting but has no interest in creating a Tumblr account of their own or engaging with the community as an active user.

“I’ve been sent [my own posts] before by real-life people who I go to school with,” she told me. “They’re like, this post reminded me of you! And I’m like ….. yeah that’s really funny… ”

Since the initial Yahoo acquisition, and increasing with each nonsensical shift in leadership and policy, Tumblr’s consistent atmosphere of dry self-awareness at the state of things has settled into a zen-like state of acceptance, perhaps even fondness.

Bec Ucich, aka Tumblr user @benepla, has been on Tumblr since 2010. You might recognize her URL from such hit posts as “I can’t wait to use snap map so everyone in my friend group knows I hang out in the sewers making little dresses for rats who hate and bite me” (2017), and a freakishly inventive set of past-life memes.

She’s observed Tumblr’s evolution from a space for pure fandom enthusiasm at the start of the last decade through its middle-decade transition into a more politically aware and social-justice-focused community. These days, Bec notes, the tenor of the site is far more casual: “Everybody left on Tumblr who’s pretty funny is a chucklefuck, such as myself, who just wants to do it because it’s fun.”

One of Tumblr’s constants over the years has been its uniquely untainted comedic character. Despite Yahoo and Verizon’s best (?) efforts, it has never been fully sullied by monetary regard, and that is what makes it, to this day, a powerful nexus of the most distilled and concentrated capital-c Content around.

But most Tumblr users I interviewed for this article seemed to be resistant—or at the very least surprised—at being called “content creators.” Even when users have loyal followings of sizes that would make any contemporary YouTuber or Instagrammer start leaping for sponsorship deals, there’s a sense that Tumblr popularity is a different beast.

The early 2010s found a handful of single-serving blogs such as Emma Koenig’s Fuck! I’m In My Twenties and Brandon Stanton’s Humans of New York being taken up for book deals by big-name publishers. A few years later, the Relatable Text Post Teens of Tumblr were raking in thousands of dollars a month in Adsense revenue, only to later be banned en masse for violating the platform’s terms of service.

With these exceptions in mind, Tumblr users have really never had the clear path to profit and success that characterizes the trajectories of popular accounts on other, more mainstream platforms. Comedians like Melanie Bracewell and Jaboukie Young-White who found initial popularity on Tumblr did not break through into real-life success until they made the jump to Twitter.

So despite the fact that Bec and Lucy are essentially doing the same thing as users on other platforms—creating stuff that people enjoy and engage with—maybe they’re right that posting original content on Tumblr is a fundamentally different proposition than doing so elsewhere, and perhaps even, these days, a more appealing one.

As a service, Tumblr’s lack of commerciality and consistent inability to successfully monetize itself is part of its whole appeal. There’s a whole genre of Tumblr posts that just screenshot and mock the bizarre hosted ads that spawn on the dashboard like mutated fish in a radioactively-poisoned river.

But it’s a loving kind of mockery—users seem, for the most part, to be genuinely grateful for the state of the site. For many, it’s a refuge from the dystopian insanity that the rest of the internet has come to represent. “It’s like anti-social social media,” says Bec, regarding Tumblr’s continued paradoxical appeal.

At its core, Tumblr has always been a platform for artists, and remains so to this day. For those who earn a living through their visual art, it can be frustrating when their Tumblr-based audience fails to provide them with levels of direct engagement conducive to promotion and monetization.

But for those who value creativity without the pressures of “hustle culture,” and wish to avoid the current-events performative outrage that has crept in, kudzu-like, and swallowed up almost every single other area of open expression online, Tumblr remains ideal.

The corollary of that, of course, being that those who appreciate that creativity without necessarily needing or wanting to express it themselves can also find happy homes on Tumblr, as spectators to a healthy culture of simply liking things.

All social networks more or less demand “authenticity” in order to establish parasocial relationships between followers and followed, and Tumblr is not necessarily an exception. But Tumblr’s focus on enthusiasm as the fulcrum point of its demanded performance of authenticity sets it apart from the aesthetic focus of Instagram and the verbal focus of Twitter.

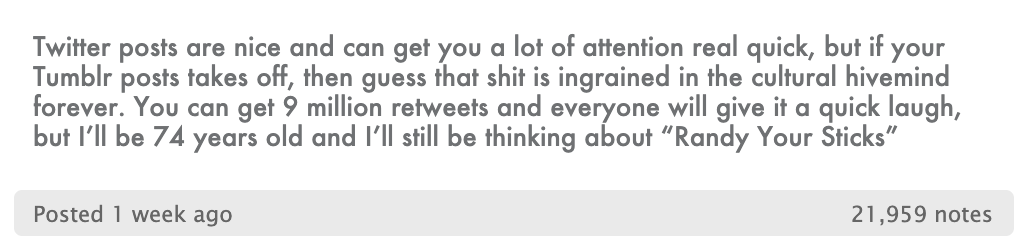

Tumblr’s persistently kaleidoscopic base of users engage with popular culture in a low-pressure, off-kilter environment—and as a result, they’re able to consistently spawn the kind of gems that lodge securely in our collective consciousness and never let go.

Compared to Twitter’s frantic feed, in which viral tweets live and die in the space of days or weeks, date-less Tumblr posts have a specifically timeless quality. They can take on mythical status as they propagate, retaining attribution while gaining collaborative additions via endless reactions and notes.

And once these posts reach the stage of their lifecycle in which they spread to other platforms, they achieve a sort of internet immortality. “I would talk to people who are quoting text posts, and I’ll know that they’ve never had a Tumblr in their life,” Lucy told me. “Because they saw a screenshot on instagram or twitter and found it funny and it became a meme.”

Tumblr isn’t a monolith, and its homegrown cringe culture has propagated and mutated in parallel with the increasingly irony-poisoned atmosphere of the internet at large.

So for some long-time users like Bec, those who gradually moved away from fandom spaces but remained on Tumblr, it might come as a pleasant surprise that the site certainly still remains a safe haven for the types of full-throttle fannish expression that characterized its early days.

Bec recalls logging on one day and seeking out blogs in the CATS fandom—or more specifically, the 1998 film of the stage musical. “Not only is there this fandom, but I was going through one of the blogs, and it evoked this like 2011 corny innocence of just like loving shit and not really caring,” she said.

For Lucy, Tumblr is a comfortable refuge, the only place she can freely mix literature-themed shitposts with nostalgic fervor for Doctor Who and Welcome To Night Vale. “I’d say it’s a pretty alive website,” she said. “The benefit of fewer people using it, and it being so much less of a culturally important thing, is that that’s almost the appeal now, that nobody’s on it.”

An anecdotal survey of my followers (1,168 of them at the time of writing) about the reasons they’re still on Tumblr revealed a fairly unified spread of answers. A majority of respondents noted that Tumblr’s inherent pseudonymity, chronological feed plus ability to ruthlessly curate that feed, and the easy-to-use tagging system were the main draws that kept them on the site.

Many users reported that even after many years on the platform, they still find that Tumblr is by far the easiest place to connect with new people over shared interests. And specifically, connecting with their peers—many people pointed to Tumblr’s perceived “distance” from the mainstream world of actors, creators, and celebrities, giving users the opportunity to freely freak out without fear of fourth-wall disturbance.

With the exception of some big names like Taylor Swift and Neil Gaiman, who joined Tumblr at its peak and haven’t left, the days when celebrities would create accounts and utilize them like they do their verified Twitters or Instagrams are long past. Similarly, mainstream media organizations that once maintained Tumblrs like they do on Twitter and Facebook have now left blogs dormant for years.

In this way, what could be perceived as its “decline” as a platform has actually increased its value in the eyes of many users. Of course, whether this phenomenon will be recognized by its new owners and actively nurtured is impossible to say—the companies who run websites do generally need to turn a profit in some way—but hey, a girl can dream.

For vast numbers of users of all ages, backgrounds, and interests, Tumblr provides an appealing alternative to the dominant structures of the social web. Using Tumblr in 2020 could be seen as a sort of countercultural statement in and of itself, an active rejection of expectations towards what platforms to use, and how to use them.

The common morbid running joke of the end of Tumblr being a foregone conclusion seems to have died down just a bit recently. In its place, a spark of hope has taken root, thanks to Tumblr’s new parent company Automattic and its commitment to “making the web a better place.” If Auttomatic has the chutzpah to keep Tumblr alive in its current state, it will continue to hold an incalculable amount of emotional and social value for young, creative people the world over.

With real-world situations prompting increasingly desperate desires for escapism, Tumblr can provide a necessary locus of release and relaxation. But its value, of course, is more than just what it isn’t, and what it points away from. Despite all the drama and discourse lurking in its corners, it’s easy to make your own Tumblr life as simple and as happy as you want it to be. There are no algorithmic threats lurking around every corner, no onslaught of promoted posts from politicians or influencers.

More than anything else, Tumblr in 2020 is a self-sustaining ecosystem. It’s a semi-sealed and increasingly fertile terrarium, a nigh-impossible perpetual-motion machine of a platform going productively psychotic in its isolation.

When considering the state of Tumblr today I like to think of Jeff Vandermeer’s book Annihilation, in which a mundane landscape is transformed into something mysterious and unknowable.

Like Vandermeer’s Area X, Tumblr can be difficult to navigate for the inexperienced, ridden with parasitic beliefs and dangerous memes. You can easily get lost in the tags, sucked into toxic subcultures, menaced by screaming skull-bears—OK, maybe not that last one.

But for us long-time users, it’s home. We’re all still in there, getting weirder and weirder, mutating all the time into new and as-of-yet unknown forms. The creativity of Tumblr visible from second-hand glimpses on other platforms is only the tip of an iceberg that encompasses enormous amounts of perpetual creative energy, generated by the affordances of the platform’s much-loved functions, traditions, and communities.

… And may it ever be thus.

If you liked this article, please help us make more! Become a patron for as little as $1 a month, or make a one-off donation of any amount.

Allegra Rosenberg is a writer based in New York City. She has written about fandom, media, tech, and history for outlets including The Verge, Business Insider, MIT Technology Review, and The New York Times. Her debut nonfiction book FANDOM FOREVER (AND EVER) is forthcoming from WW Norton.