Nielsen Ratings: An Explainer

In case you, like the rest of the world, are confused

by Flourish Klink

Nielsen ratings: you know they’re important, but you don’t know how to put them into context. We’ve got you covered.

What are Nielsen ratings for?

They’re the most widely accepted way that TV networks sell ad time to advertisers. When more people are watching TV, ad time is expensive; when fewer people are watching, it’s cheap. This is why Super Bowl ads are so special: advertisers know that the Super Bowl always has some of the highest ratings in American TV, so the time is very expensive, and they have a lot of incentive to make good ads.

What do Nielsen ratings look like?

Well, usually you’ll see something like this:

The ratings points are the percentage of all TV-owning households that tuned in. From ratings points, you can work out how many people Nielsen thinks watched a particular show. For example, if 1.2% of all TV-owning households watched Legends of Tomorrow, then about 3.14 million people watched it.

The share is the percentage of TVs that were on at the time the show aired that were tuned in. To determine how a show is stacking up against its competition, this is the number you want. Way fewer people watch TV on Friday nights than on Sunday night, so the best-rated show on Friday will have low ratings points but high share.

So… how do they determine these numbers?

That’s how many families across the United States have Nielsen “Set Meters.” Nielsen doesn’t say how families are picked, but people often report that a person comes to their house or they receive a solicitation in the mail to take part. Supposedly these 35,000 people form a representative sample of the US television viewing population, so presumably when Nielsen picks families, they’re looking out for a proportional mix of household types, races, and socioeconomic levels.

Set meters are boxes that record everything you watch, including DVRed content and cable on demand. (Nielsen also records people’s viewing habits in other, less important ways.) Nielsen doesn’t say very much about how these work, so we don’t know whether they take into account how many channels each family has access to and so on. (The system is…opaque.)

We do know that because there’s only 35,000 people in the sample and there’s a lot of TV shows to choose from, some shows can have a rating of 0.0—because so few people in the sample (if any) watched them. (But actual people, who aren’t Nielsen families, could still be watching those shows!)

Then what are sweeps?

“Sweeps” are outdated. You shouldn’t worry about sweeps.

Well, OK, here’s the short version: Before set meters existed, there were special periods where Nielsen sent diaries out to many more families than usual. They recorded what they watched in the diaries, and this determined local ad sales (not national ad sales). As a result, “sweeps week” became famous for stunt casting, crazy plot twists… anything to get those diary-keeping families to tune in.

These days, though, the set meters are more important to determining ratings, so sweeps have become less important. You really don’t need to worry about it.

What if people don’t watch live?

In recent years, there has been a crisis in US TV metrics. This is because people are watching TV:

Time-shifted (using a DVR)

Through Hulu, HBO Go, or another legal TV-viewing method

On their phones or computers (instead of on TVs where Nielsen’s set-top boxes can record it)

Pirated (look, we’ve all done it, let’s just admit it and be big about it)

To deal with these issues, Nielsen introduced new metrics: instead of just “live,” they now have Live + Same Day (everyone who watched live, plus people who set their DVR and watched it later that day), Live+3 (everyone in live + same day, plus people who watched it in the next three days) andLive+7 (you get the picture).

These days, the most important rating is the Live+3 rating. That’s the one that ad time is usually sold by. However, the Live+7 rating is getting more important.

What if people don’t watch the commercials?

“Network executives get a headache.” Why? Because since 2007, Nielsen has also provided information about how many viewers watch commercials (as opposed to fast-forwarding through them with their DVR—before 2007, it was assumed that you had no choice but to leave the commercials on, even if they were muted). So if everyone in America watched a show on their DVR and fast-forwarded through the commercials… Yeah, that show might not get renewed.

Are these ratings really the only game in town?

Not so much as they used to be! Networks have access to a lot of data beyond what Nielsen gives them, and they’re beginning to use that data to sell ad time. So for instance, most networks would like to use 35 days of viewership data to sell ad time. This is because shows usually stay available on Hulu (etc.) for 35 days after they air. Advertisers don’t like this, but it’s a negotiation, so who knows what will happen?

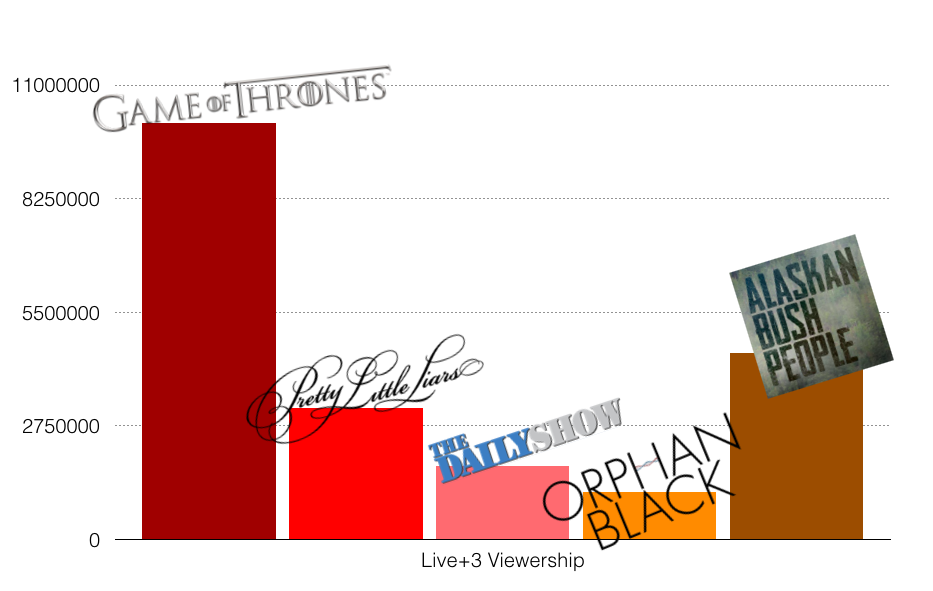

There’s also the issue that different networks have different goals for different shows. Let’s look at the Live+3 viewership numbers of some shows from June 8–14, 2015:

All of these shows got renewed for at least one more season, even though they have completely different viewership numbers (and nobody comes close to touching Game of Thrones). That’s because they air on different networks with different viewerships, and those networks have different expectations for each show.

This is why reality TV seems to have taken over networks: reality TV is cheap in comparison to scripted shows. Even though they’re literally in the Alaskan bush, Alaskan Bush People is way cheaper to make than Game of Thrones(which has to shoot in inaccessible places to show you beautiful fantasy landscapes, plus pay for CGI dragons, plus, you know, a whole writing staff).

This is also why a show like Mad Men can hold on even though it had very few viewers in comparison to, say, CSI: Your Grandma’s Attic. Mad Men was so critically acclaimed, it got renewed even when it was losing money. But that isn’t always enough (see Hannibal)—Mad Men was also the show that made AMC really mean something in the TV landscape.

But what about Netflix?

Trick question! There are several networks that don’t rely on ads to pay for their shows: Netflix (obviously) as well as HBO, Showtime, etc. (So that Game of Thrones comparison up there? Kind of apples to oranges.) So Nielsen ratings, while important for comparison to other shows, don’t apply as much.

Netflix is a weirdo, though. Unlike most other streaming video services, they actively resist Nielsen and don’t release any viewership numbers. Recently, people have been in the news for estimating their viewership as being lower than broadcast TV, but whatever.

Aren’t Nielsen ratings really outdated? Why does anyone still use them?

Simple: everyone knows what Nielsen ratings are. Advertisers know how much it costs to buy ad time on a highly-rated show or a low-rated one, and networks therefore know how much different shows are worth. It’s a delicate balance, a system that’s developed over years. Anything that destabilizes the system is going to be challenged.

The truth is, the more that we learn about people’s viewing habits through advanced technology, the more we learn they’re good at ignoring commercials. If we were to use people’s Xboxes to determine whether they were really looking at the screen while commercials were on, we might learn that most people weren’t (you have to go to the bathroom sometime). Then advertisers would pay less for ad time, because they’d know it was worth less. That’s bad for networks.

On the other hand, we might use a more accurate system to determine who’s watching a show, and discover that there’s actually a lot more people watching those late night reruns than Nielsen thought. They just weren’t part of Nielsen families. It turns out that infomercials have been radically underpaying for their ad time! That’s bad for advertisers.

When you see someone challenging Nielsen ratings these days—sometimes it’s the networks, sometimes it’s the advertisers—they often offer up new systems that they think should be used. These people always think they’ll come out on top if Nielsen ratings were abandoned. But there’s always other people who think they’d lose if we didn’t use Nielsen ratings. So it’s a long, drawn-out negotiation.

Basically: people still use Nielsen ratings because of inertia. As the TV landscape shifts, they’re slowly becoming less important. For now, though, we’re stuck with them.

What can I do to keep my favorite show on the air?

If Nielsen contacts you in any way to take part, say yes! Then watch your favorite show within 3 days of it coming out, and make sure to watch all the commercials. If you’re keeping a paper diary, actually keep it.

Watch your show in a countable way as soon as possible after it airs, ideally within 3 days of its first airing. Even if you aren’t a Nielsen family, watching on Hulu or another official streaming service is countable. Don’t just download it from your download community and think that somehow makes a difference (duh).

Tweet about your show, especially live, while it’s actually on air. “Twitter ratings” are a thing. Tumblr ratings are not. They aren’t the most important aspect of whether a show gets renewed—but if your show’s on the cusp, it could (possibly) (maybe) make a difference.

Oh, and if you’re really salty, you could always hate-watch things in a non-countable way. NCIS has enough viewers already. You don’t need to throw them a bone at the expense of Orphan Black or whatever. Watch it late, watch it in ways that it can’t be counted, whatever. (Realistically, this is probably not going to make any difference at all, but it might make you feel better…)

Disclaimer: ratings are really complex and actually nobody knows 100% of all things about them, and Nielsen doesn’t actually share basically any information, plus this post is super simplified, so you know, if you have more specific questions ask them and we will try to answer!

Flourish Klink co-created and co-hosted Fansplaining from 2015-2024. Formerly, they worked in fan culture and audience research for major media franchises; now, they are pursuing the priesthood in the Episcopal Church.