The Hillary Fandom

Politics as fandom, and fandom as politics

by Elizabeth Minkel

Can a politician have a fandom? Politics are about issues and platforms and beliefs; wonks—including much of our media coverage—tend to believe that political races are first and foremost about policy. But elections, presidential ones in particular, are also about emotion: we often vote with our feels. When we talk about candidates, we invoke words that can be swapped with “fan”—the term “supporter,” for example, gets a lot of play in British sports as well as transatlantic politics. We talk about party members, about the loyal base, about groups of people united around a personality rather than a platform or a set of beliefs (though these things are intertwined).

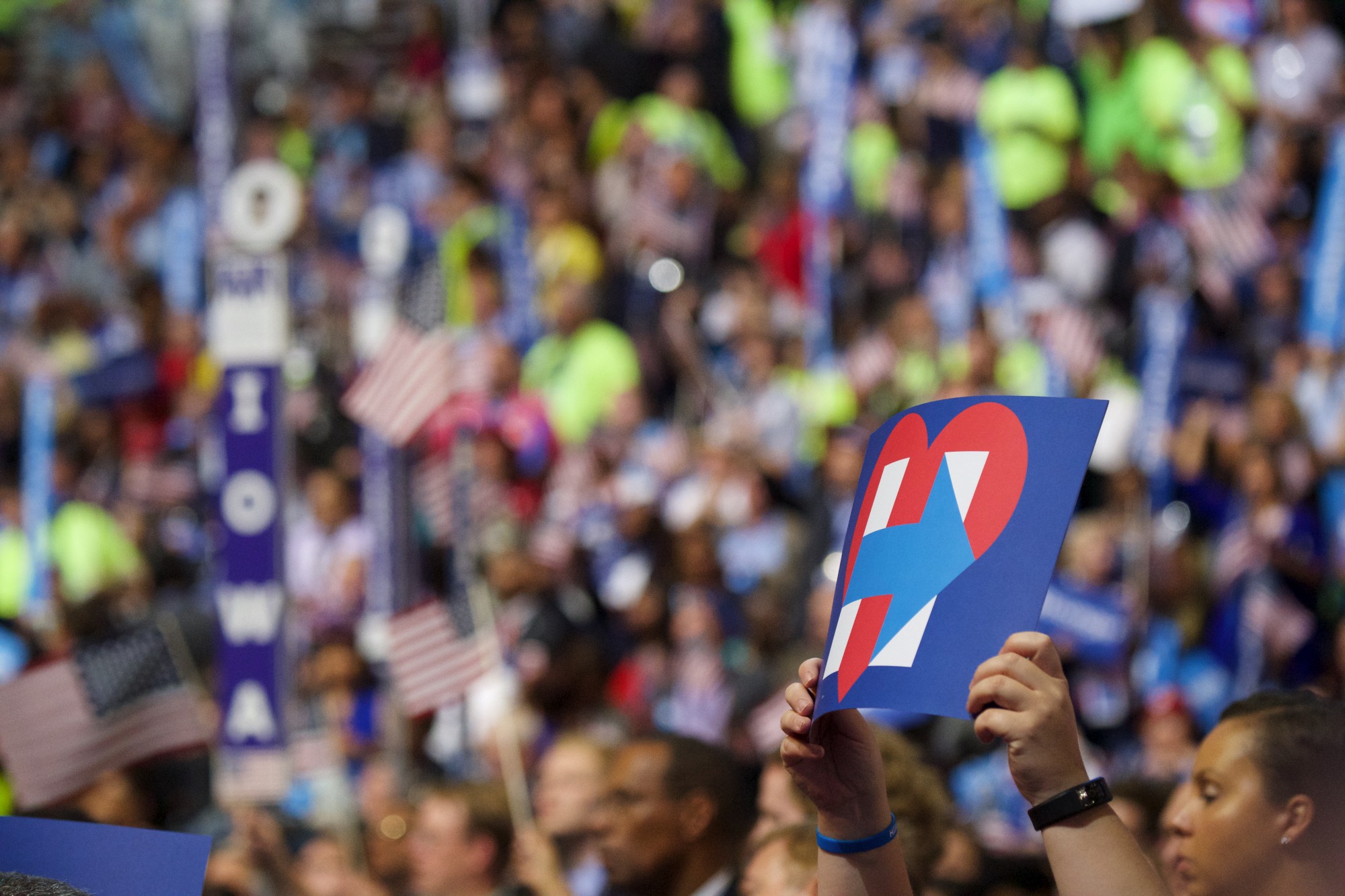

Political rallies can resemble concerts or sporting events: voters dress up and wave signs just like the people in body paint at a football game, or girls pressed up against the crush barriers at a 1D concert. Our social media feeds are full of quotes and images and gifs and memes about the candidate we love (or the one we hate). Collective emotion, directed at a single point, is on display. Are they fans? Is that fandom?

Last year in the (blissfully short) lead-up to the UK general election, teenage girls started adorning Ed Miliband with flower crowns and heart-eye emojis. The nerdy, somewhat awkward Labour leader—whose closest brush with pop culture prior to this was the consensus that he looked like an Aardman Studios character—made for a deeply unexpected teen idol. The media boggled over the emerging “Milifandom,” the (mostly) young women who were vocal supporters of Miliband and Labour and were using the language and imagery of modern fan culture—flower crowns and all—to express it.

Labour, of course, lost the election. (Buzzfeed got in touch with some of the girls from the Milifandom this past spring, and their love for the now-former leader was still strong.) But the Milifandom provided an interesting lens to look at political supporters in an age where ideas about fandom are being folded into mainstream discourse at a breakneck pace.

Last summer, Bernie Sanders fans started cropping up on my Tumblr dashboard. At the time, Tumblr itself confirmed that the candidate was dominating the platform. Like the Milifandom, Tumblr’s Bernie supporters were giving him what I like to think of the full fandom treatment: just as we devote equal parts squee and analysis to our favorite shows, the presidential politics on my dash were a mix of substantive discussion about Bernie and a celebration of the idea of Bernie—and if politicians can have a “fandom,” it’s the latter that’s key.

In January, as we inched closer to American humans actually casting a vote after 8,000 years of talking about the election, The Guardian ran a piece about Bernie supporters and another politicians’ fans, the hardcore Trumpites (two groups with some demographic crossover). The word “fandom” appears only in the title—“The white man pathology: inside the fandom of Sanders and Trump”—and the word “fan” only glancingly, comparing lingerers after a Trump rally to fans after a concert. But it was fascinating to see these supporters framed as “fandom,” even briefly.

During the primary, Bernie had a fandom; Hillary’s supporters, many of whom reported keeping quiet for fear of getting piled on (myself included) didn’t present any sort of fannish front. If Bernie was the character fans loved to spin fun headcanons about, Hillary was the character you could see fans killing off to get your faves together. Within the liberal sphere of the internet, memes like the pop-culture comparisons one, which had 0% to do with reality and 100% to do with sexism, got a ton of traction.

Our presidents over the past three decades, for the most part, have inspired fan-level enthusiasm. One might argue that this isn’t a good thing: perhaps our country could be better governed if we cared more about policy and less about the cult of personality. There was Ronald Reagan, of course, and Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. Bush v Gore was a lackluster contest, a sort of same v same that, with the view of history, feels almost impossible to wrap our heads around in light of what happened next. But by the start of the Iraq War and then Bush’s reelection, his supporters loved him with the fervor that I loved Barack Obama. A long line of politicians with that special something, an ineffable charm, the sort of appeal that the objects of fandom have: even when you’re frustrated with them, they pull you back in.

What about Hillary, though? The same words crop up again and again. Wooden. Robotic. Fake. Panderer. Hard to relate to. “I apparently remind some people of their mother-in-law or their boss, or something,” she told Henry Louis Gates in 1996. “She laughs,” he writes. “But she isn’t joking, exactly.” You don’t like her voice, especially when she shouts. So shrill! She nags. She scolds. She’s smug—she’s a know-it-all. She doesn’t smile enough. God, why is she smiling like she’s at her granddaughter’s birthday party?

She is the female character you just can’t connect to, the one who’s always ruining your good time. She does the work, and she lets you know she’s done it. She sits at the front of the class and she doesn’t slouch. She’s Hermione Granger. She’s Leslie Knope. She’s—wait. Don’t we all love Hermione? And Leslie? I see them both on my dash every single day. But then, when I think back to the start of Harry Potter, or the first season of Parks & Rec, it was so much easier to love Harry, 0r Ron Swanson. Hermione and Leslie had to work for it—they had to earn our affection.

I spend a lot of time on Tumblr—probably no more than my fandom friends, but a whole lot more than my friends outside of fandom. Tumblr, despite the popular belief, is not dominated by teens, but by 20-somethings, mostly younger Millennials, leaving me, on the oldest end of the Millennial range, sometimes at odds with what I’m seeing. My dash over the past few months has revealed the detritus of a bitter primary and the legacy of Hillary Clinton’s narrative: people parroting perceptions of her that were spun up before they were born. They find her innately unlikeable because they have literally never lived in a world where people were encouraged to like her. Sometimes this turns to apathy, but sometimes this turns to hatred. I see the same rhetoric from seemingly liberal Tumblrites that I see on my Trump-loving cousin’s Facebook page. Both groups have a very loose relationship with the facts, but a whole lot of passion. The Hillary anti-fandom.

If you spend a lot of time on Tumblr, you’ll know what an inherently political space it is: far beyond call-out culture, Tumblr is full of critical reframings and passionate liberal debate. The word “discourse” has been so overused it’s come to lose most of its meaning. And in fannish spaces on Tumblr, no one shies away from political conversations—we dive in and deconstruct and push our characters and ourselves to do better. The disconnect between this culture and the narratives around Hillary have been striking. For many, she hasn’t even been cast in the role of “problematic fave”—it’s outright hatred, a refusal to believe she could have any ideological overlap with the youthful left on Tumblr. In reality, her platform and their beliefs overlap constantly.

After Hillary clinched the nomination, a hashtag emerged on Twitter: #IGuessI’mWithHer. I appreciate the fact that lots of people who weren’t supporting Hillary grudgingly came around, but it frustrated me all the same. It’s the lesser of two evils—how? She’s very flawed but she’s better than Trump—OK? What presidential candidate isn’t very flawed? Why do we have to couch our statements about her with things like that? Is it because she doesn’t have that charm, that easy likability, that artifice that makes you think, “I don’t care what he’s actually going to do, I want to believe in him.” I felt that way about Bill Clinton. I felt that way about Barack Obama. But I’ve been embarrassed to say that I feel that way about Hillary Clinton, even though I do—her bad narrative has snagged me, too.

At New York Comic-Con this past weekend, tucked in the bowels of the nightmare that is the Javits Center, I carted around a bag of buttons emblazoned with Hillary’s logo, that now-iconic red arrow. They were fresh from Nerds for Her, a campaign started by Paul DeGeorge of the band Harry and the Potters to stir up fannish enthusiasm for Hillary, and to channel fans’ values into excitement for the campaign. I’d affixed a “Wizards w/ Her” button to my NYCC badge; on the other buttons, Hillary’s logo was on Cap’s shield, beneath Hamilton’s silhouette, above a TARDIS, and in front of the Vulcan salute and the words, “The Only Logical Choice.”

It probably marks me as a miserable journalist to say that I find approaching strangers at conventions incredibly intimidating. But having to ask them about politics was even more daunting. I was giving the buttons away, but I had no sense of how they’d be received. For a gathering of hundreds of thousands of people just weeks before an incredibly contentious election, NYCC was notably devoid of politics. I saw shirts and buttons urging people to elect such luminous politicians as Randy Marsh (South Park, Colorado), Ash Williams (Elk Grove, Michigan), and Harvey Dent (Gotham City, Gotham…State?). (I know Harvey Dent is a politician, though based on how that whole thing turned out, maybe not someone you want to vote for?)

But I approached a Harry Potter first—of course I did—and he squinted at me myopically as I asked if he was supporting Hillary. “No,” he snapped, frowning. I saw a Rey a few minutes later, and asked her the same question. Her nose wrinkled. “I…I don’t think so.” Other hesitant inquiries were met with glares and nos. I approached a middle-aged woman in a Star Trek uniform, thinking surely the crossover between middle-aged female Trek fans and Hillary supporters was strong. When I asked her, she looked like I’d asked if I could murder her child. “I’m not voting for ANYONE,” she said, raising her voice indignantly. “OK!” I said, trying to sound as cheerful as possible to keep myself from lecturing her about the moral messages of Star Trek and Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations until the end of time.

I finally found a 40s-era Cap with a sign that said “Make Captain America Great Again.” “Hey Cap, want some Hillary buttons?” I shouted. I knew now that my, “Are you supporting Hillary?” question wasn’t winning anyone over. “Hell yeah!” Cap shouted back, and he and his friends on the line grabbed them eagerly. “Oh, what are you giving out?” the woman behind them said, leaning forward. When she saw the logos on the buttons, she pulled her hand back like she’d been burned. “Oh, I don’t do real politics,” she said.

She’s not alone. Viewership is down in the NFL right now, and I assumed it was because a lot of football fans are like me, deeply conflicted about the brain injury epidemic and the NFL’s slow (in)action to do something about it. But a recent poll suggested that people are tuning in less because the protests of Colin Kaepernick and other players: of 1,000 football fans surveyed, a third said they were less likely to tune in because of the quarterback’s peaceful protest during the National Anthem. (NFL executives blame “a confluence of events” including the presidential election in a clear effort to downplay the impact of both the protests and the concussions.)

My immediate reaction around hearing this was essentially, “WHAT BABIES.” ‘Politics are ruining my football’—it goes hand in hand with a convention full of people celebrating deeply political stories, characters who fight against and for the political strife of their fictional universes, saying things like, “I don’t do real politics.” “Vote Harvey Dent…no, I’m not voting in the presidential election, why would I?” We all “do real politics,” whether we like it or not. Some people just have the privilege to act like they don’t.

I see this argument regularly in my own fannish spaces, when the discourse turns to racism, or homophobia, or misogyny, or other issues that are inherently political. These conversations crop up again and again in the context of characters or some fictional universe we love, of for fanfiction writers, in the worlds we build upon. “This is my escape.” “I’m just here to have fun.” These are the common mantras. For many people, from marginalized groups in particular, simply living is made political. Some people don’t get to turn that off, even if they, too, just want to have fun.

When I tell people outside fandom that fans are political, that they care deeply about real-world issues and how they’re reflected in fiction, they often seem pretty surprised. Is it because we seem so much more invested in fictional worlds than our own? Is it because the common perception of a fan is an uncritical person, a slavish devotee, not the “let’s deconstruct this shit” kind of fandom I’ve known for close to two decades now? My experiences at NYCC proved me wrong, to some degree—lots of fans don’t want to engage. This was disheartening, to say the least: we care about stuff more than the average person, and is there anything more worth caring about than a presidential election, and this godforsaken election in particular?

But I know there are fans who care out there. And we are experts at crafting a narrative: at taking a tiny spark and making it blossom into an entire world. I’m so glad we’re all fired up about beating Trump, but to really make it stick, we’ve got to be fired up about voting for Hillary, too. Fuck bad narratives: we’re fans, we’ll do whatever we want with this story. It’s not enough for me to say #I’mWithHer—I’m a member of the Hillary fandom.

This article is brought to you by Fansplaining’s patrons. If you’d like to help us publish more writing like this in the future, please consider pledging as little as $1 a month.

Elizabeth Minkel is the editor and host of Fansplaining. She’s written about fan culture for WIRED, Atlas Obscura, The New Yorker, the New Statesman, and more. She co-curates “The Rec Center,” a weekly fandom newsletter, with fellow journalist Gavia Baker-Whitelaw.